Struggling to survive

Up to the late 19th century, most families worldwide had many children.

But unsanitary conditions, poor nutrition and weak health systems meant that children faced uncertain prospects of surviving their early years.

And for most of those who made it to adulthood, life was short.

Then, things changed – as advances in nutrition, science and technology fuelled social and economic development and improved health care.

Access to modern contraceptives, education and the labour market helped spark women’s empowerment. People chose to marry and have children later. Living standards improved, bringing better nutrition, clean water and sanitation to more and more people.

More children survived.

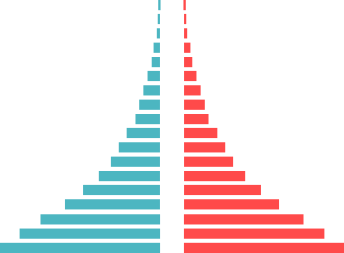

This is a population pyramid

Each bar represents the number of people in an age group.

Note: The population pyramids shown here are intended to depict broad patterns only, and do not represent data from an actual country.

Today, this is what the population pyramid looks like in the world’s poorest countries.

Choosing to have fewer children

Access to contraception and sexual and reproductive health care gives women control over their fertility – and their lives. Better health care and public education lower mortality and improve prospects for children.

Birth rates begin to fall.

These trends transform the structure of populations.

Transforming the structure of populations

More families choose to have fewer children.

As child mortality falls, the adolescent population balloons.

These young people are poised to enter working age.

More people live longer. The population overall gradually ages.

What is the demographic dividend?

Increasing life expectancy, declining child mortality and declining fertility transform the structure of populations.

With the right investments, these changes can accelerate sustainable development.

When the working-age population expands to exceed the numbers of the very young and very old, the stage is set for a demographic dividend.

If this large population of young people is healthy, educated, empowered and employed in decent work, they can boost economic growth in one generation.

It doesn’t happen on its own. To capitalize on a demographic dividend, you need to invest in young people.

Empowerment

To pursue opportunities, all people need to live free from violence and coercion. They need health care, including sexual and reproductive health services.

The key lies with women and girls steering their own lives. And for that, having the freedom to decide if and when to have children is indispensable.

Education

People generating new opportunities and capitalizing on them are the engine of a demographic dividend.

Lifelong access to learning is essential to prepare young people to enter the workforce – and to keep older workers prepared for change.

Employment

It’s not enough just to educate young people – they need jobs. Channeled into productive activities, their knowledge, skills and efforts can fuel a demographic dividend.

To build prosperity and growth in a sustainable way, everyone – young and old, men and women – needs opportunities for decent work that pays a living wage.

In some countries, the demographic transition has already happened. For others, it lies in the future.

Working-age population, 2018

This map shows the share of each country’s population that is between the ages of 20 and 64 – working age.

Source: United Nations, Popular Division, World Population Prospects: 2017 revision; World Bank, World Development Indicators; and ILO, ILOSTAT.

Note: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is expressed in constant 2010 US$. Labour productivity is expressed in constant 2011 international $ in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms. An international dollar has the same purchasing power as the U.S. dollar has in the United States. A PPP exchange rate is the number of units of a country’s currency required to buy the same amounts of goods and services in the domestic market as a U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.

Please select country for detailed view

Select country from map or menu

Source: United Nations, Popular Division, World Population

Prospects: 2017 revision; World Bank, World Development Indicators; and ILO, ILOSTAT.

*Note: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is expressed in constant 2010 US$. Labour productivity is expressed in constant 2011 international $ in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms. An international dollar has the same purchasing power as the U.S. dollar has in the United States. A PPP exchange rate is the number of units of a country’s currency required to buy the same amounts of goods and services in the domestic market as a U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.