We

1.8 Billion young people

We

1.8 Billion young people

Are the

Changemakers, peacebuilders, leaders

Missing

Trust, support, recognition

Peace

Depends on us

The missing peace

Independent progress study on

youth, peace and security

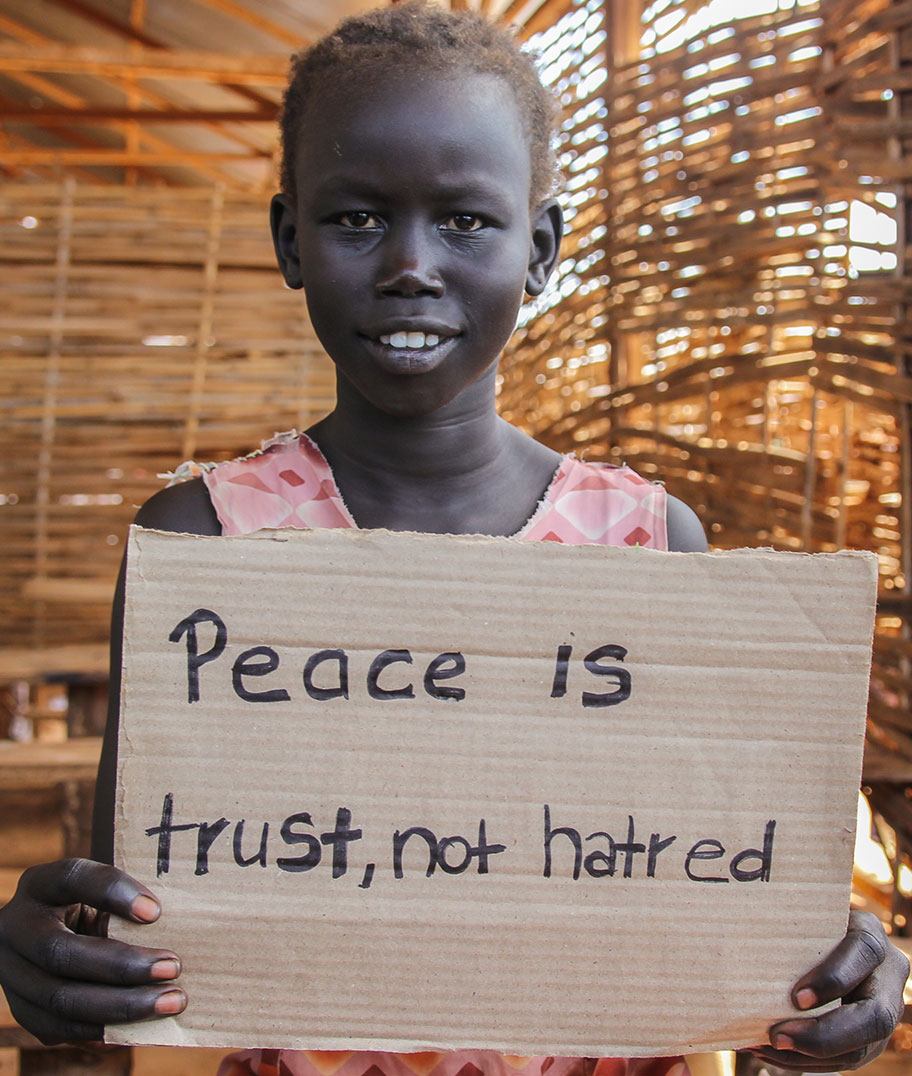

Across the globe, there are extraordinary young people creatively seeking ways to prevent violence and consolidate peace. However, many are frustrated by the tendency of their Governments and international actors to treat youth as a problem to be solved, rather than as partners for peace.

Throughout the world, young people consulted for the Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security expressed that they have lost faith and trust in their Governments, the international community and systems of governance that they feel excluded from, contributing to a strong and ongoing sense of injustice.

This must be addressed in order to support and benefit from young people’s contributions to peace, and to realize the potential of 1.8 billion young people.

© United Nations/Amanda Voisard

© United Nations/Amanda Voisard

In 2015, the Security Council adopted UNSCR 2250, the first resolution entirely dedicated to recognizing the importance of engaging young women and men in shaping and sustaining peace. UNSCR 2250 calls on Member States to include young people in their institutions and mechanisms to prevent violent conflict and to support the work already being performed by youth in peace and security. In addition, the Resolution requests the Secretary-General to “carry out a Progress Study on the youth’s positive contribution to peace processes and conflict resolution, in order to recommend effective responses at local, national, regional and international levels.”

© UNFPA/Aral Kalk

© UNFPA/Aral Kalk

The Progress Study was conducted as an independent research process, led by Graeme Simpson and an Advisory Group of Experts, all appointed by the Secretary-General of the United Nations. They were supported by the United Nations and numerous partners from civil society, foundations and intergovernmental organizations. A UNFPA and Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO) Secretariat was put in place to support the Study. The Study was developed through a participatory approach that involved face-to-face consultations with a total of 4,230 young people, including 281 focus group discussions in 44 countries, as well as 7 regional and 6 national consultations. In addition, there were 25 country-focused studies, 20 thematic submissions from partners, 5 online thematic consultations, a global survey of youth-led civil society peacebuilding organizations, and mapping exercises of Member States’ and UN entities’ work focused on young people in relation to peace and security.

The designations employed and the presentation of material on the map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNFPA concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties.

A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

* References to Kosovo should be understood in the context of Security Council Resolution 1244 (1999).

Stereotypes and policy myths

In 2016, an estimated 408 million youth(aged 15-29) resided in settings affected by armed conflict or organized violence.

This means that at least 1 in 4 young people are affected by violence or armed conflict in some way.

We young people have three opportunities: to die assassinated, to migrate or to join a gang.

Northern Triangle

© UNICEF/Alaoui

© UNICEF/Alaoui

For young people consulted throughout the Progress Study, peace and security are more than just the absence of violence, and concern all societies. Young people stress the importance of addressing the symptoms of violence, as well as the underlying causes of corruption, inequality and social injustice. Young people are clear that conflict itself might be unavoidable, but that violent conflict can be prevented by ensuring social and political channels are in place to navigate a diversity of opinions and perspectives.

Peace for young people is also deeply personal, associated with well-being and happiness. Young people involved in the research for the Study describe that peace manifests itself in physical, psychological and institutional forms, and is tied to issues of belonging, dignity, hope and the absence of fear. Peace is also seen as fundamentally gendered, particularly in relation to personal safety, with sexual and gender-based violence as a core concern.

© WVI/Stefanie Glinski

© WVI/Stefanie Glinski

For young people, peace and security are not only related to the absence of violence. Peace is about development and human rights, and is essential for the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Youth, peace and security is also directly linked to women, peace and security (UNSCR 1325), especially its emphasis on including civil society, opening avenues of participation for traditionally excluded stakeholders, and underscoring the pivotal role of young women for peace. In their work, young people address different phases of peace and conflict – from preventing the outbreak of violence to post-conflict peacebuilding – demonstrating their commitment to peacebuilding and sustaining peace.

We young people have the power to place ourselves at the nexus between good governance, peacebuilding and development.

South Sudan

© UNICEF/Daniele Volpe

© UNICEF/Daniele Volpe

Widespread stereotypes associate young people, and particularly young men, with violence. In reality, the vast majority of young people are not involved, or at risk of participating, in violence.

There are three main misconceptions regarding young people:

These myths have triggered a “policy panic,” producing un-nuanced policy responses that involve hard-fisted law enforcement and security approaches, which are counterproductive and not cost-effective. These approaches further alienate young people and diminish their trust in their Governments and the multilateral system.

How young people are contributing to peace and security

© UNDP/Shahem Abu Ghazaleh

© UNDP/Shahem Abu Ghazaleh

© UNICEF/Sokhin

© UNICEF/Sokhin

© UN Photo / Mark Garten

© UN Photo / Mark Garten

© Momoko Sato, UNV / Tim Jenkins, UNDP

© Momoko Sato, UNV / Tim Jenkins, UNDP

© Andrew Esiebo, UNICEF

© Andrew Esiebo, UNICEF

© Gilbertson, UNICEF"

© Gilbertson, UNICEF"

Our actions, although simple, contribute significantly to the construction and manufacture of peace.

Yemen

© UNICEF/Ashley Gilberston

© UNICEF/Ashley Gilberston

Youth-led organizations working on peace vary greatly in size, as do the scope and impact of their work. A survey undertaken by United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY) and Search for Common Ground offers a picture of their work, often at the local level, in contexts of instability or violence. These organizations have a deep understanding of local conditions and meaningful community relationships, and, as a result, can work with populations that other actors cannot easily access.

Most youth-led organizations surveyed depend heavily on volunteers and are modestly funded or underfunded. Half of the 399 organizations that answered the survey operated with less than $5,000 per year, and only 11 per cent did so with more than $100,000.

Young people predominate among those who deal with conflict resolution. They are very active and this manifests itself in everything: in politics, in the economy, in the social sphere.

Georgia

© UNFPA

© UNFPA

Youth-led organizations are an important source of leadership and agency for young people. But young people also participate and exert their leadership elsewhere in diverse institutions and arenas of civic life, civil society organizations and remote communities.

Without young people working on peace and security, the decision makers will not understand our needs. Young people need to be taken seriously and held responsible on their [youth-led] projects.

France

© UNFPA/Ben Manser

© UNFPA/Ben Manser

Young people have long been at the forefront of political and social change, challenging the status quo through peaceful protest, artistic expression and online mobilization. While such movements have sometimes faced violent reactions from the State, peaceful expressions of dissent remain some of the most important tools for youth-based movements struggling for political change and justice.

If we had opportunities to exercise our power and agency, then our potential could be transformed. What's making us vulnerable is that lack of opportunity.

East and Southern Africa

Countering the violence of exclusion

© UNFPA/Omar Kasrawi

© UNFPA/Omar Kasrawi

During the consultations and focus groups undertaken for the Study, young people expressed that they feel excluded from meaningful civic and political participation, and that they mistrust systems of patronage and corrupt governance that lack the will and capacity to address their grievances. This has driven young people’s demand for greater participation in electoral processes and policymaking through youth councils, assemblies and parliaments, as well as decision-making forums at the local, national, regional and global levels. This situation has also led many young people to withdraw from formal politics, and instead create alternative avenues for participation. For political participation to be meaningful, young women and men need to be broadly represented and consulted in all arenas, without being subjected to co-optation, manipulation or control by political parties. Young people’s participation in formal peace processes remains limited, reduced only to informal although diverse venues.

© UNFPA/Guadalupe Valdes

© UNFPA/Guadalupe Valdes

Irrespective of country context and levels of violence, concerns over economic well-being and livelihoods are key issues in relation to peace and security for youth. Contrary to widely accepted assumptions, youth unemployment has not been proven to lead to violence. Instead, violent conflict is more likely fueled by experiences of inequality and exclusion based on identity, ethnicity or gender. Young people often feel that current employment opportunities fail to offer a sense of meaning or identity, leading to frustration. Interventions targeted at improving young people’s economic stake in society must go beyond just jobs to address deeper grievances and perceived injustices, and allow young people to participate in the decisions that affect their lives.

© WVI/Mark Nonkes

© WVI/Mark Nonkes

Education features universally as a core peace and security concern for young people. Educational institutions are critical sites where young people as “beneficiaries” interact with the State or non-state actors as “providers”. Young people have high hopes for the transformative role of education via both formal and non-formal mechanisms in building peace. They think education based on the transmission of values of peace is vital and that teaching critical-thinking skills, non-violent methods to address conflicts and celebration of diversity should be prioritized.

We need to engage young people at a younger age – the curricula for children should also include peacebuilding, so they grow up with this mindset.

Fiji

© UNFPA

© UNFPA

Programming in peace and security has tended to prioritize young men, regarding them as perpetrators of violence or “spoilers” of peace processes, while young women tend to be seen as victims in need of protection. It is important to address young women’s disproportionate experiences of sexual and gender-based violence, as well as the violence faced by sexual and gender minorities. A critical component of this involves supporting youth peacebuilding work that is focused on promoting positive, gender-equitable and non-violent masculine roles and identities.

We are never safe. In the street, you hear all forms of sexual harassment. In the house, men are very creative to make us suffer.

Tunisia

© UNICEF/Adriana Zehbrauskas

© UNICEF/Adriana Zehbrauskas

Young people themselves are also victims of numerous forms of violence: state repression; terrorism; gangs and organized crime; gender-based violence and violence against young migrants, refugees and internally displaces persons (IDPs). Beyond physical violence, young people pointed to violations of their fundamental rights as a source of grievance and insecurity. Without the appropriate protection mechanisms and equitable delivery of social services, including sexual and reproductive health or psychosocial support, feelings of uncertainty and instability among young people might lead to self-destructive coping mechanisms and a deepening of the mistrust between young people and the State.

From a demographic dividend to a peace dividend

Click below for the Security Council Report

Click below for the full version of the Progress Study

Extensive information on the research undertaken for the Progress Study is available at http://youth4peace.info/ProgressStudy.