Protecting girls from harmful practices

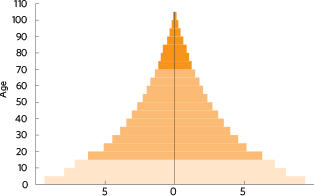

Every day, an estimated 47,700 girls are at risk of being married before age 18.

In some parts of the world, a girl who begins menstruating may soon be married against her will. Protecting a girl from child marriage requires interventions that reach her before age 10—before puberty, when vulnerability to this harmful practice accelerates.

The International Center for Research on Women evaluated 23 child marriage-prevention programmes and found that the initiatives that fostered information, skills and networks for girls yielded the strongest and consistent results. Programmes that had the least impact on reducing child marriage were those that attempted to address the problem only at a macro-level, by, for example, changing laws.

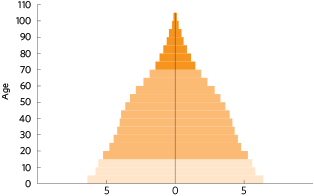

A body of evidence is emerging that programmes that help poor girls stay in school and protect their health help reduce the incidence of child marriage. Results show that girls in communities with education, gender- and rights-awareness and skills training intervention programmes are less likely to be married.

Girls around the world are also vulnerable to sexual, physical and psychological violence in and around schools, and in public spaces. Action to prevent gender-based violence— and to make it safer for girls to attend school— must encompass prevention and response activities and “whole-of school” approaches that involve students, parents, teachers, community members and local organizations in finding solutions.

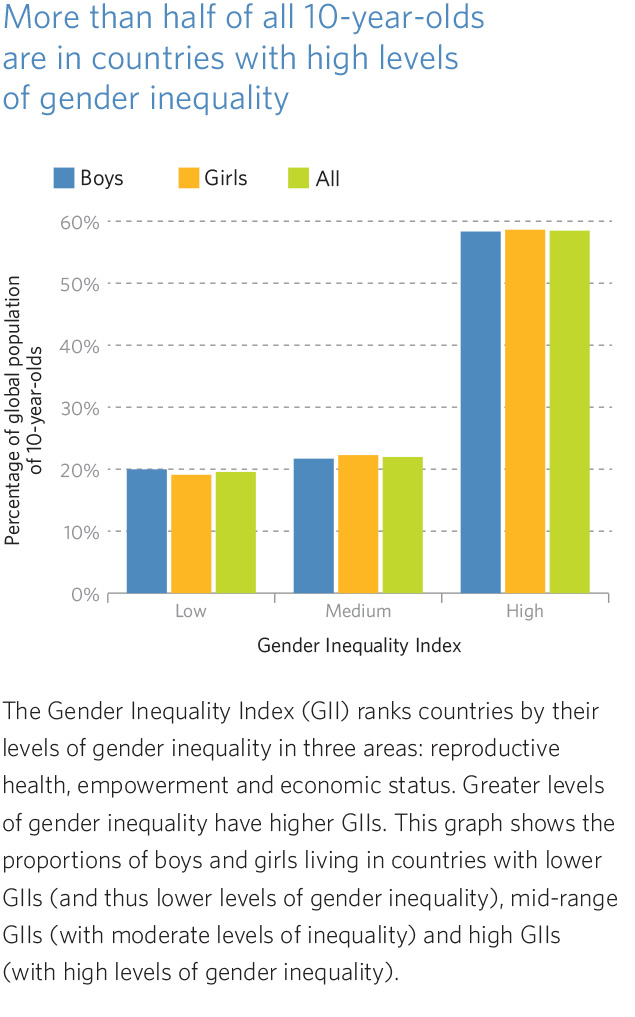

Tearing down barriers to gender equality

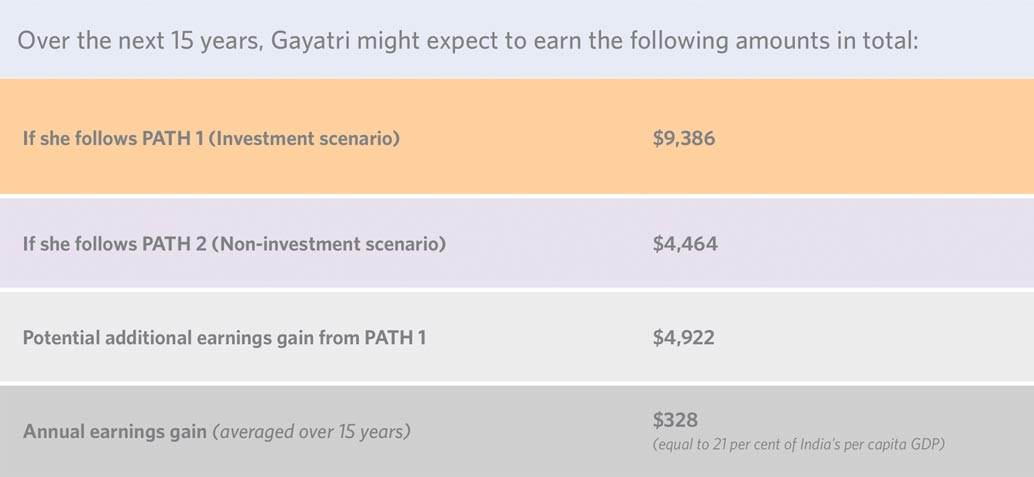

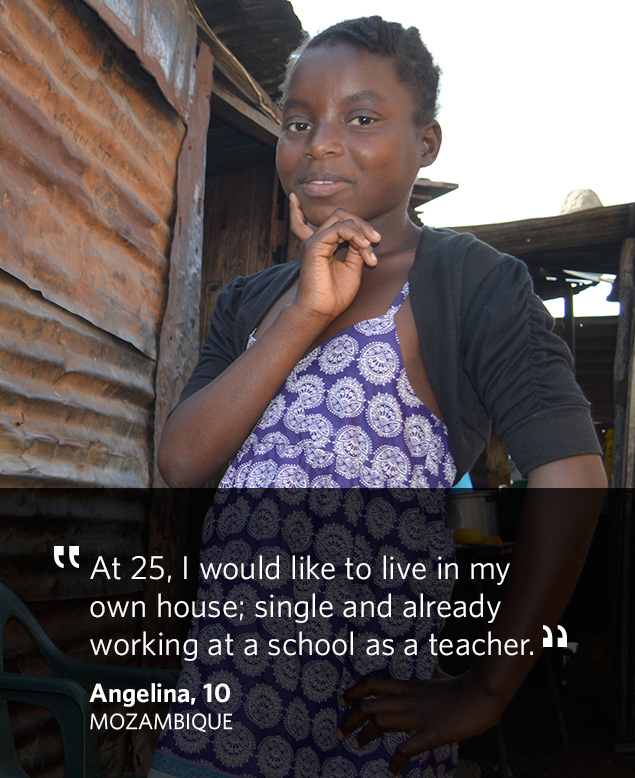

Empowering 10-year-olds socially and economically benefits girls themselves and has the potential to transform their communities. But empowerment requires tearing down the numerous and complex barriers to equality and changing negative attitudes.

Men and boys can be important allies and supporters of girls’ empowerment. Engaging them in programmes that promote gender equality can therefore contribute to lasting change.

Programmes that recognize that gender roles and relations are intertwined with cultural, religious, economic, political and social circumstances are more likely to have a positive impact. They are based on the idea that gender relations are not static and can be changed.

Scale up

Through small-scale and pilot efforts around the world, 10-year-old girls have gained access to services and support that have helped build their human capital, skills, agency and autonomy. These attributes in turn have helped delay marriage and pregnancy and keep them on a safe and healthy path to adulthood.

At the same time, community-level actions aimed at promoting gender equality, and local and national efforts to prevent and address gender-based violence have begun to yield positive results.

The challenge now is to scale up and adapt successful interventions so that they reach more girls in more places and effect change in more communities.