Mothers and daughters of Haiti, living in the grip of violence

Anxious and scared, a mother phones a hotline run by a women’s centre in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. “I can’t sleep at night,” she tells Eleyina, the support worker on the line. “I have to watch over my daughter to make sure she isn’t raped.”

The situation in Haiti is desperate. Gang violence has forced more than half a million people across the country to flee their homes. The capital reverberates with gunshots day and night, and sexual violence is carried out with impunity.

The lawlessness and violence hinder an effective humanitarian response.

Here, in this deeply personal series of portraits, women and girls share their insight into the stark reality of life today in Port-au-Prince, while UNFPA and partners work around the clock to prevent and alleviate suffering.

Esther, whose name has been changed for protection, was raped when she was four months pregnant and sleeping in a public square with her six children, having been forced from home. She received counselling from a UNFPA health centre, but her situation is still dire.

You can hear her tell her story in this video.

UNFPA and partners are powerless to prevent gang violence, but they can help increase safety for people like Esther. For instance, UNFPA has arranged for lighting to be installed in displacement camps, and local partner FOSREF is part of a security initiative that provides personnel to patrol the camps through the night.

“San vyolans lavi pi bél,” the signs say. “Life is more beautiful without violence.”

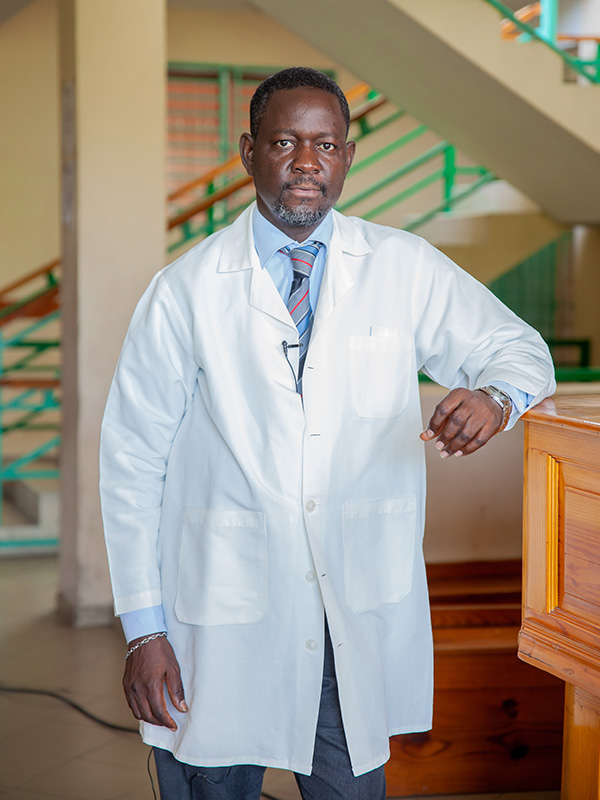

“Since insecurity has risen in the country,

we are attending to many more cases of rape.”

It is estimated that only 25 percent of rape survivors are able to access medical assistance within 72 hours, a vital time period for accessing post-exposure prophylaxis, a short course of HIV medicines taken soon after possible exposure.

Mobile clinics supported by UNFPA have been deployed to displacement sites in order to increase access to reproductive health and protection services, and to ensure that survivors know how to access holistic support.

UNFPA is equipping health facilities and hospitals with essential supplies, including kits for the clinical management of rape, as well as life-saving maternal health kits containing supplies for obstetric emergencies.

Giving birth was already risky before the current escalation of violence – Haiti has the highest maternal mortality rate in the western hemisphere, with 950 women dying from complications during pregnancy, childbirth and the aftermath every year.

Now, with the violence limiting access to maternal health care, and a critical shortage of supplies and staff, childbirth is even more dangerous for the estimated 84,000 pregnant women across the country.

Mothers-to-be are fearful for the future of their children before they’re even born. Twenty-six-year-old Lovely, pictured here, has just gone into labour. She is being supported by midwives at the Eliazar Germain Hospital in Port-au-Prince.

“Even though I'm in a lot of pain, I'm happy because this is my first child and I was excited at the idea of having a baby,” she says. “But when there's shooting, I’m really scared.”

“After giving birth, I was really happy. Because of the C-section, I did not feel too well, but I am delighted to have my first child,” she says. “With the situation in the country, I am especially afraid of kidnapping and armed gangs. My biggest wish for my baby is that I leave the country with him because I don’t want him to grow up here.”

For many young people growing up in Haiti, education has ground to an abrupt halt.

Monica and Bianca both miss their homes. “Gang members attacked our house, and we were forced to flee,” says Monica, who now lives at a camp. “We couldn't save a thing. I haven't been to school for eight months. Once, the gangs tried to attack the camp, and we were really scared. Sometimes I cry because I don't want to live in these conditions.”

Bianca describes how gangs took what they wanted from her family’s home, then burned it down. She is staying at the same camp as her friend Monica. “I don't feel safe here because you always hear gunshots. Sometimes people are killed in front of the camp fence,” she says.

“I am supposed to be in fifth grade, but I don't go to school anymore because my school is in the same neighbourhood as where we lived.”

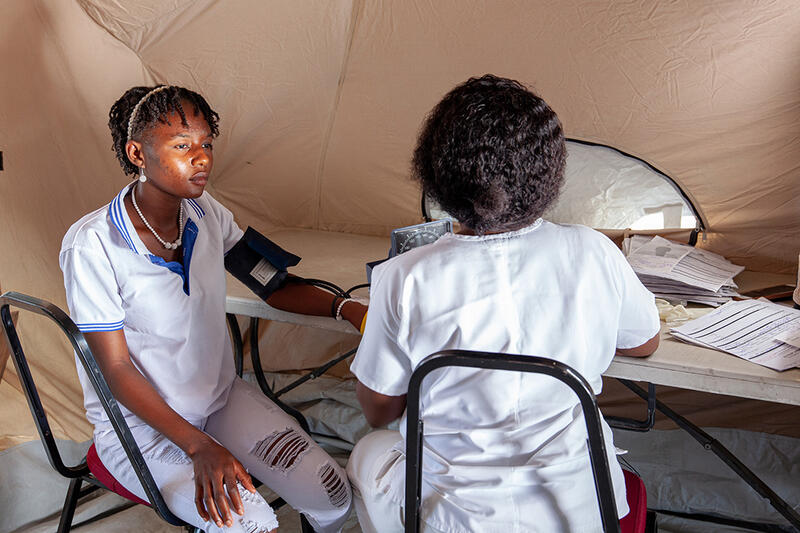

Both girls accessed services at a mobile clinic today. “I'd like to become a nurse myself and help children,” says Bianca. “I wish gangs didn't exist anymore. To try and forget about the situation, I play with my friends in the camp."

As night approaches in Port-au-Prince, fighting intensifies and fears increase. The UNFPA-supported patrols set up at camps, while the hotline pings with text messages and midwives deliver babies against a backdrop of violence.

Life continues, yet at the same time is on hold.

More from UNFPA’s work on the ground

Mobile clinics have been deployed to eight displacement sites to provide reproductive health and services and to help prevent and respond to violence. They are a vital support, as fewer than half of health facilities are operating at normal capacity. The health-care teams are inundated with needs when they arrive at each camp.

“I want to see zero kidnappings, zero men beating women, zero victims of violence, zero psychological harm. In the meantime we'll continue to do what we do: We'll keep fighting, keep working.”

Find out more: https://www.unfpa.org/haiti