A wish for every mother: A safe birth and a promising future

In an ideal world, every mother-to-be would have access to a skilled midwife and could give birth in a safe and peaceful environment, feeling confident that she can take her newborn to a secure, warm home and provide everything the child needs.

Sadly, too many women lack these assurances.

Around the world, a woman dies every two minutes during pregnancy or childbirth. Some are at increased risk, including women living in remote areas with limited access to services, those who experience discrimination, and those living amid conflict or climate crises.

UNFPA is striving to achieve the ideal scenario for every woman, by investing in midwives and training, including in emergency humanitarian situations, and by equipping maternity wards and mobile health teams – supporting women wherever they are when they need care.

Here, meet women from across the world who are benefiting from the quality care.

Supporting displaced women in Armenia

“I didn’t know which son to run to save first,” says Mari, 25, describing the panic when bombs started falling in Karabakh – the region at the heart of a territorial conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan – in September 2023. “One was in school and the other at kindergarten.”

Mari, who was nine months pregnant at the time, became one of an estimated 2,070 pregnant women who had to flee for safety across the border in Armenia.

When Mari and her family arrived in Armenia, they stayed at a UNFPA-supported safe space. Mari received health care, emotional support and essential supplies to help prepare for the birth away from home.

Baby Gabriela is the latest addition to the family of five, with everyone now living in a one-bedroom apartment in Abovyan. “We left behind a fully furnished home and couldn’t bring anything with us – but we brought our most valuable treasure,” Mari says of Gabriela.

UNFPA has provided reproductive health kits to clinics in towns along the border, including in Abovyan, and is extending supplies to cover more areas in order to meet the increased demand on maternal health services as families remain unable to return home.

Taking the fear out of childbirth in Latin America

Yolimar, a native of Venezuela, lives with her husband on a rural indigenous reservation in Colombia. Living remotely and being part of an indigenous community are two factors that can increase discrimination and disadvantage when it comes to accessing maternal-health services.

Fortunately for Yolima, she received quality care and support when it came time to give birth. She traveled to San Andrés Hospital in Tumaco, where she was assisted by the head nurse of the delivery room, Elisa Coral Guerrero, who had participated in UNFPA training.

UNFPA training on human rights and leadership is designed to recognize and strengthen midwifery and obstetric care as a health specialism. Midwives are key to increasing safe births and ensuring maternal services are equitable and free from violence and discrimination.

The training is crucial. In Latin America, it is estimated that around 43 per cent of women experience obstetric violence, the abuse and mistreatment of women during childbirth, including being forced into procedures against their will. Midwives trained by UNFPA said they had observed that racism is among the factors that determine how women are treated.

Nurse Elisa notes that women in the Tumaco area are particularly vulnerable. “Tumaco is a remote area compared to other parts of Colombia and historically neglected. Political abandonment has increased the risks for indigenous women,” she says. “Midwives have a very important role. It’s important to highly respect and value all women. Childbirth and maternal care must be human, decent, and it must be intercultural.”

Helping pregnant women of Gaza in unthinkable conditions

Malak, 22, from Gaza City, was three months pregnant when the war in Gaza began in October 2023. She went from planning the arrival of her first child, including the joy of choosing new clothes and baby items, to being displaced time and again, putting her at risk.

Throughout her pregnancy, Malak struggled to access antenatal care. As weeks of bombardment turned into months, she struggled to find enough food each day.

When Malak’s contractions started, the maternity ward in Rafah was the nearest facility, but she knew the hospital was overwhelmed, so she traveled three hours to a facility in Al-Nusairat. Beds were hard to come by there as well.

“As soon as I sat down, they got me back up from the bed because there was an emergency case more urgent than mine – she was having a Caesarean section,” she says. “So, I got up and gave her my place, even though I was also in labour. When she finished, they let me use the bed.”

Malak now worries about how to keep her son warm, fed and safe. “It would have been different back home in Gaza City,” she says. “Khalid is the first grandchild of the family – they would have welcomed him with a big celebration. I would have returned to home-cooked chicken soup and many other things.”

UNFPA is working to support women and girls in Gaza, including the 155,000 pregnant women and new mothers living with unimaginable stress. Support over the last six months has included deploying midwives and providing essential supplies, as well as UNFPA’s first mobile maternity unit, which arrived in Rafah on 9 April. Stationed at the Al Mawasi Field Hospital, the unit can provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care, including Caesarean sections and blood transfusions.

Rafah is the main hub of the humanitarian response in Gaza and has some of the area’s last functioning health facilities. This includes the Al-Helal Al-Emirati Maternity Hospital, which is now the main facility for pregnant women in Rafah, managing around 60 deliveries every day. Attacks in Rafah could turn this and other facilities from places of hope into rubble – putting at the lives of tens of thousands of pregnant women at risk.

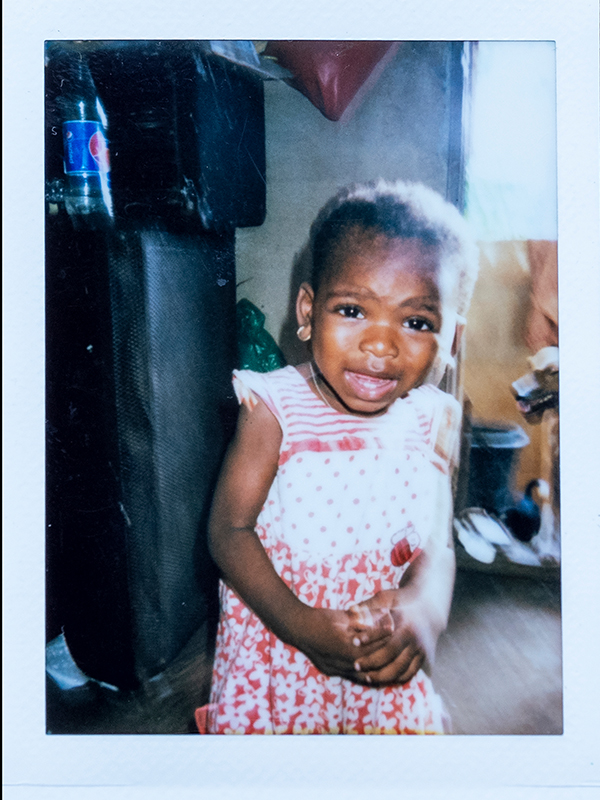

Providing opportunities for young mothers in Nigeria

Nigeria is one of the world’s fastest-growing countries, with a young population and a high birth rate, including teenage pregnancies.

UNFPA supports four Young Mums’ Clinics across the city of Lagos, connecting young mothers with education and job-training opportunities, in addition to providing maternal health care, baby-care supplies, family planning and psychosocial support. The education and training initiatives are especially key for teen mothers, the majority of whom do not return to the classroom after giving birth.

The clinics have transformed the lives of hundreds of young women and their children. Kehinde is among them. When she became pregnant, her family encouraged her to go to a nearby clinic, and she took their advice. “My parents are a very important part of my life,” she says. “When I was pregnant, they never left me once.”

Since 2015, the clinics have supported 998 young mothers, including assistance with 557 safe deliveries by skilled birth attendants. “The Young Mums’ Clinic was really a safe space for me throughout my pregnancy period,” says Kehinde. “I got my confidence back.”

Kehinde will return to school to continue her education.“I wish to be a psychologist. I want to help people understand themselves,” she says. “I want to be successful in life so I can take care of my parents in their old age and also take good care of my daughter.”

Ensuring safe births amid climate crises in the Philippines

As an archipelago, the Philippines is severely affected by extreme weather events, with the island nation bracing itself for around 20 major storms and typhoons on average each year. Climate change is increasing the intensity and destruction of the storms, with super typhoons on the rise.

In 2022, UNFPA provided the first mobile birthing clinic in the Philippines in order to reach women in disaster-affected areas. When super typhoon Rai – known locally as Odette – struck, Mariel was the first mother to give birth at the clinic, known as Women’s Health on Wheels, in Southern Leyte.

A second mobile clinic followed and the successful model was adopted by the Department of Health. Ten primary health care vans were rolled out which included sexual and reproductive health services.

The mobile clinics are now a key part of the Department of Health's strategy to reduce maternal deaths. They are vital in reaching women and girls in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas across the Philippines, allowing women to access immediate maternal-health services, even amid a disaster.

Saving lives with maternal waiting homes in Ethiopia

Azmera, a pregnant woman living in Neqsege, a mountainous area in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, knew she would have trouble getting to a health clinic if she waited until she went into labour, with the challenges of terrain and distance.

And so, ahead of her due date, she has traveled to a maternal waiting home – a residential home near a maternity clinic, with maternal services on hand. Now, she knows she will have access to quality care when she needs it.

UNFPA supports 54 maternal waiting homes across Ethiopia so that women who live in remote areas, or who have a high risk of complications, can have access to care. The women generally arrive at the homes around a week before their due date.

The homes are a resounding success. Studies in Ethiopia show that women who access maternal waiting homes are 80 to 91 per cent less likely to die. The homes are a key part of UNFPA’s overall efforts to increase access to quality sexual and reproductive health services in Ethiopia. Other recent initiatives included the deployment of 222 midwives and the support of 10 mobile health teams last year.

Abat Getahun, who benefited from one of the maternal waiting homes when she gave birth, says the facilities have solved many challenges for pregnant women, noting that before the life-saving homes were created, “women were giving birth on the road.”