- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

Number of FGM-related arrests, cases brought to court, and cases of convictions and sanctions in all Tier 1 countries and trend since 2015.

Accelerating Change

UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation

To safeguard progress and accelerate the decline of FGM, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) last year launched Phase III (2018-2021) of the Joint Programme on the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation: Accelerating Change.

The Joint Programme is the world’s largest and most comprehensive effort seeking to eliminate FGM, and plays an important role in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 5, Target 5.3, on the elimination of harmful practices, including FGM.

In 2018 the Joint Programme continued its comprehensive approach to changing harmful social norms, creating enabling environments through policy and legislation, supporting access to comprehensive services, and empowering communities to drive social change.

560,271

women and girls received

health services related to FGM

231,375

women and girls

received social services

83,812

women and girls

received legal services

83,068 girls

in 4,258 communities

gained skills and knowledge to advocate for their rights and become agents of social change

Holding governments accountable for meeting their obligations to eliminate FGM

Strengthening interventions that build the agency of women and girls

Expanding engagement with men and boys to promote gender equality

Improving community surveillance after public declarations of FGM abandonment

Developing a framework to measure social norms change

Focusing on alarming trends including medicalization and cross-border FGM

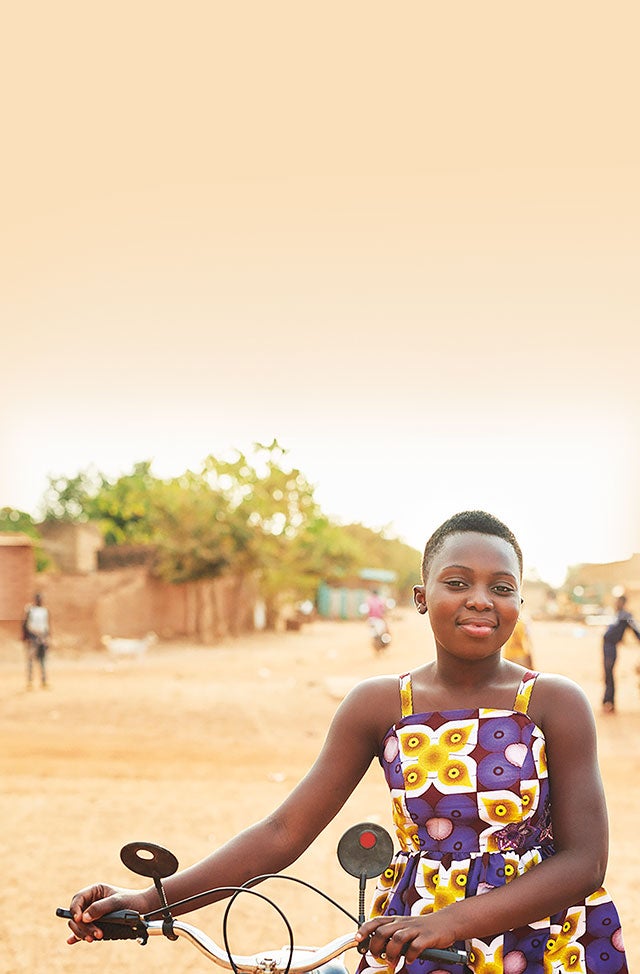

They are divided into three tiers according to needs and priorities. In 2018, funding constraints initially limited programme interventions to Tier 1 countries. Uganda and Mali received financial and technical support by the middle of the year.

Tier 1 countries

Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan

Tier 2 countries

Eritrea, the Gambia, Guinea and Mauritania

Tier 3 countries

Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Somalia, Uganda and Yemen

An enabling environment for the elimination of FGM requires not only enacting laws and making policies, but also fully implementing them.

In 2018, the Joint Programme worked with governments to ensure that the necessary budgets and technical know-how are in place to put laws and policies into practice and monitor their effectiveness. The Joint Programme fostered cooperation between governments, civil society organizations and community networks to develop policies and programmes, and worked at the regional level to promote accountability.

400+ participants from 33 countries convened at the 2018 African Union-Joint Programme conference in Burkina Faso to galvanize political action to eliminate FGM

At her mother’s insistence, Dr. Eman Hashim, now 37, was spared from undergoing FGM. Once almost universal in Egypt, FGM is now declining there. Stronger penalties against the practice were enacted following the death of a 13-year-old girl who was cut in a rural hospital in 2013.

While most older women have undergone the practice, only 61 per cent of girls aged 15-17 have been cut. But medicalization of the procedure is on the rise, with more than 80 per cent of procedures now being performed by health care providers in secret.

The Joint Programme has been working to change the situation. In 2017, after years of lobbying, approval was granted to integrate information about the harm caused by FGM into the curriculum of medical education programmes. “It’s a start,” says Dr. Hashim, who has worked with UNFPA on gender-based violence.

Number of FGM-related arrests, cases brought to court, and cases of convictions and sanctions in all Tier 1 countries and trend since 2015.

Laws that clearly state that FGM is unacceptable can contribute to ending the practice. While all Tier 1 countries, aside from Sudan, have national legislation criminalising FGM, law enforcement is weak in some. In others, fear of punishment has driven FGM underground.

Number of Tier 1 countries with evidence-based, costed national action plans to end FGM, 2018.

Number of Tier 1 countries with budget lines to end FGM, 2018.

Number of Tier 1 countries with national FGM data, 2018.

Number of Tier 1 countries with national coordinating bodies, 2018.

Number of Tier 1 countries with annual review of FGM programmes, 2018.

Political commitment is not enough to eliminate FGM. Budgets, technical support and advocacy are needed to develop and implement laws and policies and coordinate among national stakeholders, including target communities.

The Joint Programme worked with the African Union to convene governments, civil society and development partners in Burkina Faso in October 2018.

The conference culminated in commitments by AU member States to adopt an AU-wide initiative on the elimination of FGM; condemn all harmful practices, including those performed by health providers; develop costed national action plans to support services and law enforcement; strengthen coordination to address the root causes of FGM; and invest in alternative livelihoods for traditional excisors.

“We, Ministers from 22 African Union Member States with Indonesia and Yemen... note with great urgency the need to galvanise political and community action, strengthen and implement legislative frameworks, mobilise and invest resources, strengthen accountability and partnerships to accelerate the elimination of female genital mutilation.”

– Ouagadougou Call for the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation

The Y-PEER youth network uses peer education and activities like theatre and games to engage and educate adolescents and young people, like these in Egypt, about sexual and reproductive health, gender-based violence and harmful practices including FGM. © Luca Zordan for UNFPA

Source for all figures: UNFPA-UNICEF FGM Joint Programme database, 2018.

Eliminating FGM requires a transformation of social and gender norms to support the human rights of women and girls. In 2018 the Joint Programme continued to educate, encourage dialogue, engage in consensus-building, and help mobilise communities to collectively and publicly abandon the practice – with follow-up to ensure lasting change. Emphasis was placed on addressing traditional gender roles and power relations that contribute to perpetuating FGM.

2.8 million people in 2,455 communities across the 8 Tier 1 countries participated in public declarations of FGM abandonment

Akande Adeola, an FGM survivor, participated in the Frown Challenge campaign in Nigeria, home to 20 million girls and women who have undergone FGM – one tenth of the global total.

The campaign encourages Nigerians to post a picture of themselves frowning, along with thoughts and experiences with FGM, on Twitter or Instagram. Within six months of its launch, the campaign had reached more than a half million Nigerians and engaged celebrities and participants from around the world. The most popular posts of its first year were honoured at a 2018 award ceremony, which also recognized community service organizations working on the issue.

Organisers say the Frown Campaign empowers people to share their thoughts about FGM. “As people speak out, more people become aware that FGM is still being practised. Innocent parents are aware of why they have to protect their children against FGM.”

© Pacovibs

TV, radio, print media, social media and performing arts can carry messages that spark behaviour change. Senegal’s #TouchePasAMaSoeur (Don’t Touch My Sister) campaign, in partnership with the youth-led Parole Aux Jeunes (Youth Talk), used social media to engage people from all walks of life against FGM and child marriage. Docudramas produced in Egypt offered entertainment and education tools for religious leaders to use in their advocacy to end FGM.

“Language is a weapon,” says Senegalese rapper Baaba Maal, whose song ‘Cri du Couer’ (Cry of the Heart) denounces FGM and violence against women and girls. “I’m not using it to destroy, but to build bridges and bring people together.”

The Joint Programme supported girls’ clubs, community dialogues, school-based programmes, mentorship, alternative rites of passage programmes, and other opportunities for girls to participate in comprehensive sexuality education, human rights training, life skills training and professional development. These initiatives empowered girls to gain skills and knowledge to build their own lives and create change in their communities.

Men and boys in Senegal participate in a community conversation on FGM. © UNFPA Senegal

The Joint Programme engages men and boys to champion gender equality and the elimination of FGM by questioning and challenging power dynamics in their own lives, in their communities and in society.

Through a partnership with the MenEngage Alliance, networks and coalitions to promote positive masculinity and improve health were introduced and expanded in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Senegal.

Number of communities where religious leaders made public statements delinking FGM from religious requirements, Tier 1 countries.

Number of communities where community or traditional rulers publicly denounce FGM, Tier 1 countries.

Number of communities where public declarations of FGM abandonment have been made, Tier 1 countries.

Number of communities where community-level surveillance mechanisms have been established following public declarations of FGM abandonment, Tier 1 countries.

The Joint Programme supports interventions that open up a space for communities to critically reflect on FGM as a rights violation – and ultimately make a collective declaration of FGM abandonment. The Joint Programme also supported the establishment of post-declaration surveillance mechanisms to ensure communities do not go back to practising FGM.

Source for all figures: UNFPA-UNICEF FGM Joint Programme database, 2018.

Through extensive work with governments and civil society, the Joint Programme ensures that girls and women at risk of or affected by FGM have access to quality, comprehensive services for prevention, protection and care.

Comprehensive services include health care, education, police and justice services, and social services – within a system that can coordinate service delivery across sectors. Services can contribute to promoting positive social norms that keep girls and women healthy and intact, including by creating a cadre of advocates for FGM abandonment among the service providers that women and girls rely on.

Over 560,000

women and girls

received FGM-related health services, over 231,000 received social services and nearly 84,000 received legal services

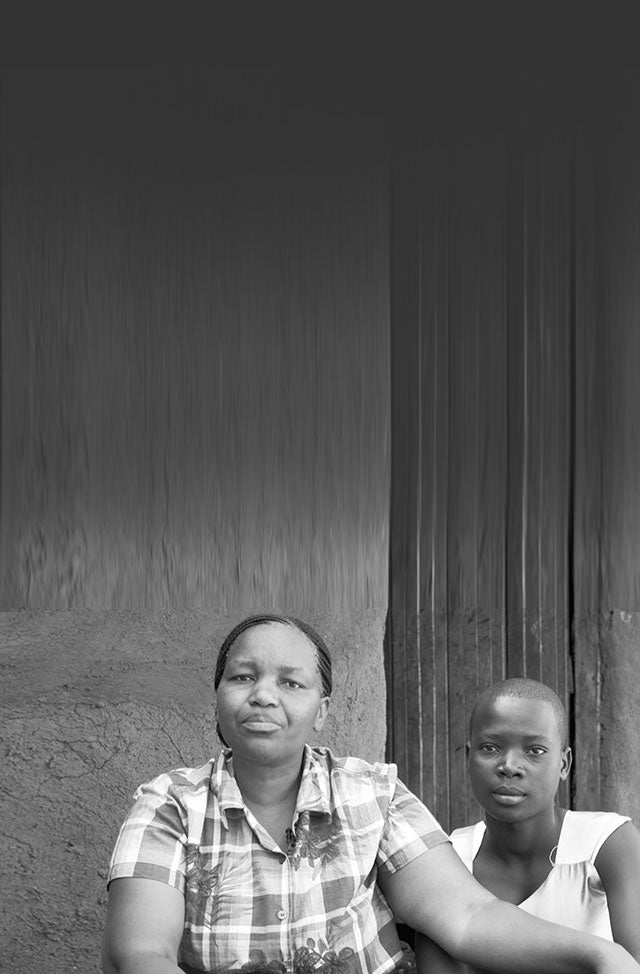

Human rights activist Rhobi Samwelly, herself an FGM survivor, runs two safe houses in Tanzania’s largely rural Mara region. She doesn’t want other girls to go through the ordeal she experienced at age 13, when she nearly bled to death after being cut.

In Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda, where cutting typically occurs around puberty, girls are old enough to understand the harm FGM causes, and often resist. Where families and communities won’t relent, safe houses like Ms. Samwelly’s offer a refuge.

They also work to persuade parents to respect their daughters’ wishes to remain intact, avoid child marriage and continue their schooling. “We are not stopping,” says Ms. Samwelly. “We keep visiting those families, talking to them so we can have reconciliation.”

In neighbouring Kenya, some 1,000 centres and safe houses were instrumental in protecting about 5,030 girls from FGM in 2018.

Through the Joint Programme’s support, women and girls received quality services to meet their sexual and reproductive health needs and protect their human rights.

Since Phase I started in 2013, nearly 4.3 million women and girls have received services.

Number of girls and women who received health services related to FGM, including prevention services, Tier 1 countries.

Source: UNFPA-UNICEF FGM Joint Programme database, 2018.

Number of girls and women who received social services related to FGM, Tier 1 countries.

Source: UNFPA-UNICEF FGM Joint Programme database, 2018.

Number of girls and women who received legal services related to FGM, Tier 1 countries.

Source: UNFPA-UNICEF FGM Joint Programme database, 2018.

Training for service providers empowers them to become community role models, counsellors and advocates who champion the elimination of FGM

Dr. Yohannes and his team provide reproductive health services for women and girls in a region of Ethiopia where most undergo infibulation, a severe form of FGM that brings high risks of complications during the cutting and throughout life. Their hospital has partnered with field practitioners in rural communities to identify women and girls at risk, offer local support, and find ways to bring patients to the hospital © Luca Zordan for UNFPA

Improving countries’ capacity to generate and use FGM-related data and evidence is critical to creating better policies and programmes and strengthening health, social protection and justice systems to support the abandonment of FGM. In 2018, the Joint Programme focused on measuring social norm change, and established a global knowledge hub – a platform for sharing the programme’s FGM content across countries and their diasporas.

The Joint Programme provides technical guidance to governments conducting national surveys, plays a key role in analysing data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), partners with key stakeholders to develop thematic studies and guidelines for improved interventions, and provides technical and financial support for country-specific studies and evaluations.

68 million girls are at risk of FGM between 2015 and 2030, according to new estimates issues by UNFPA

Safe houses like the ones operated by Rhobi Samwelly in Tanzania are helping to protect girls from FGM and working to change minds about the practice. But getting girls to these safe houses is often a challenge. In rural Tanzania, for instance, large swaths of land remain unmapped. When a call for help comes in, safe house staff may have a hard time finding their way to the girl.

Crowd2Map Tanzania is working to change that. Since 2015, the organization has coordinated a network of volunteers to fill in blank spaces on rural Tanzanian maps. Crowdsourced maps show girls the way to the services they need, while guiding service providers like safe house workers to girls and women at risk of, or affected by, FGM.

The crowdsourced maps are also filling critical data gaps to help target FGM-related programming.

As more and more communities abandon FGM, programming needs to zero in on remaining hotspots. Since household surveys offer regional-level data at best, district-level data generated through the mapping project are indispensable for identifying the communities where FGM is still practised. Then, outreach and services can reach the women and girls who need them most.

The Joint Programme’s value proposition includes four elements: economy, efficiency, effectiveness and equity

In Ethiopia’s remote Afar region, FGM prevalence has fallen sharply in areas where the Joint Programme has been active, down to 31 per cent in some districts compared to 91 per cent in the region as a whole. © Luca Zordan for UNFPA

These elements are represented by interventions targeting the most marginalised populations; by joint planning and coordination of the interventions between the Joint Programme and key stakeholders such as government, civil society and donors; and by the high budget utilization rate and savings achieved.

In the Tier 1 countries, the Joint Programme used criteria such as poverty indicators, FGM prevalence, the number of girls at risk and other social indicators to examine who is being left behind and why – and to target efforts toward communities with the highest levels of deprivation among children and women, along with FGM prevalence above their countries’ national average.

All eight Tier I countries conducted joint planning, monitoring, review and reporting activities. Common surveillance systems are under study, and the Joint Programme continued to strengthen governments’ capacities to coordinate actions to end FGM. Meanwhile, coordination between UNICEF and UNFPA increased the power of the two organizations to convene, influence and cut costs related to programming and administrative issues.

With the launch of Phase III, the Joint Programme continued to face two global challenges:

Rapidly growing populations in countries where FGM is practised are leading to a significant increase in the number of girls at risk of FGM.

Decreases in FGM prevalence are difficult to measure, as national-level surveys do not reflect local realities. The Joint Programme’s work often targets smaller areas, and its impact does not show up on national-level surveys.

At the same time, the Joint Programme contended with a series of programme-specific challenges:

Insufficient national budgets to support meaningful programme implementation

African Union campaign to end FGM will create an accountability mechanism to monitor national resource allocation

Weak data management systems where databases for real-time data collection and reporting are lacking

Advocate for and strengthen capacity of national data systems to integrate FGM indicators

Reporting and prosecution remain low despite policies and legislation banning FGM

Assess barriers to accessing legal services and strengthen community surveillance mechanisms

Weak referral systems linking community members and FGM-related services

Map out strategic interventions to institutionalize and sustain services, as part of systems-strengthening approach