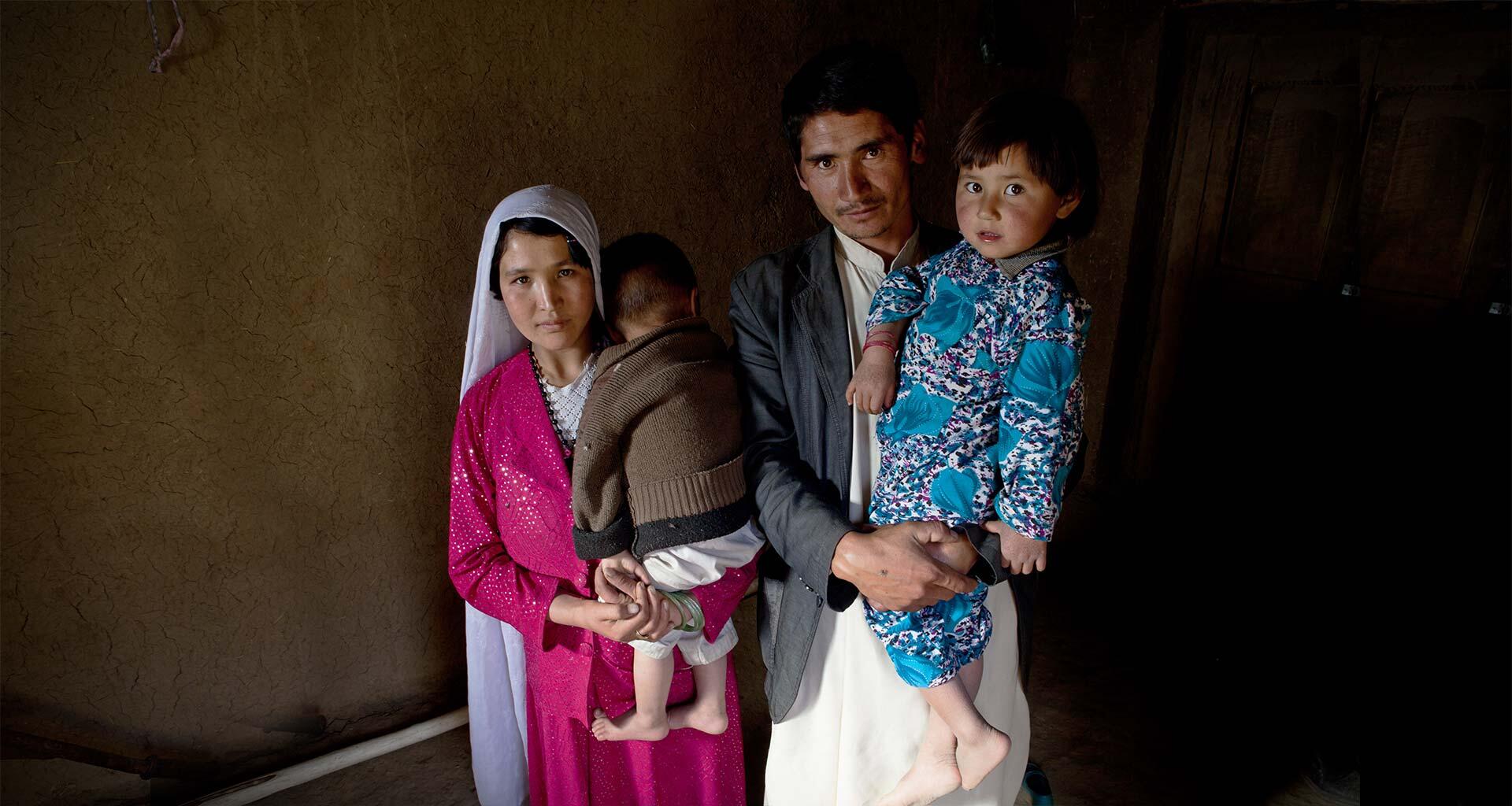

The day a woman gives birth is the day she is most likely to die.

Approximately 800 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth – one woman every two minutes. For every woman who dies, between 20 and 30 will experience childbirth injuries, infections or disabilities. Most of these deaths and injuries are entirely preventable.

Making motherhood safer is a human rights imperative. It is at the core of UNFPA’s mandate.

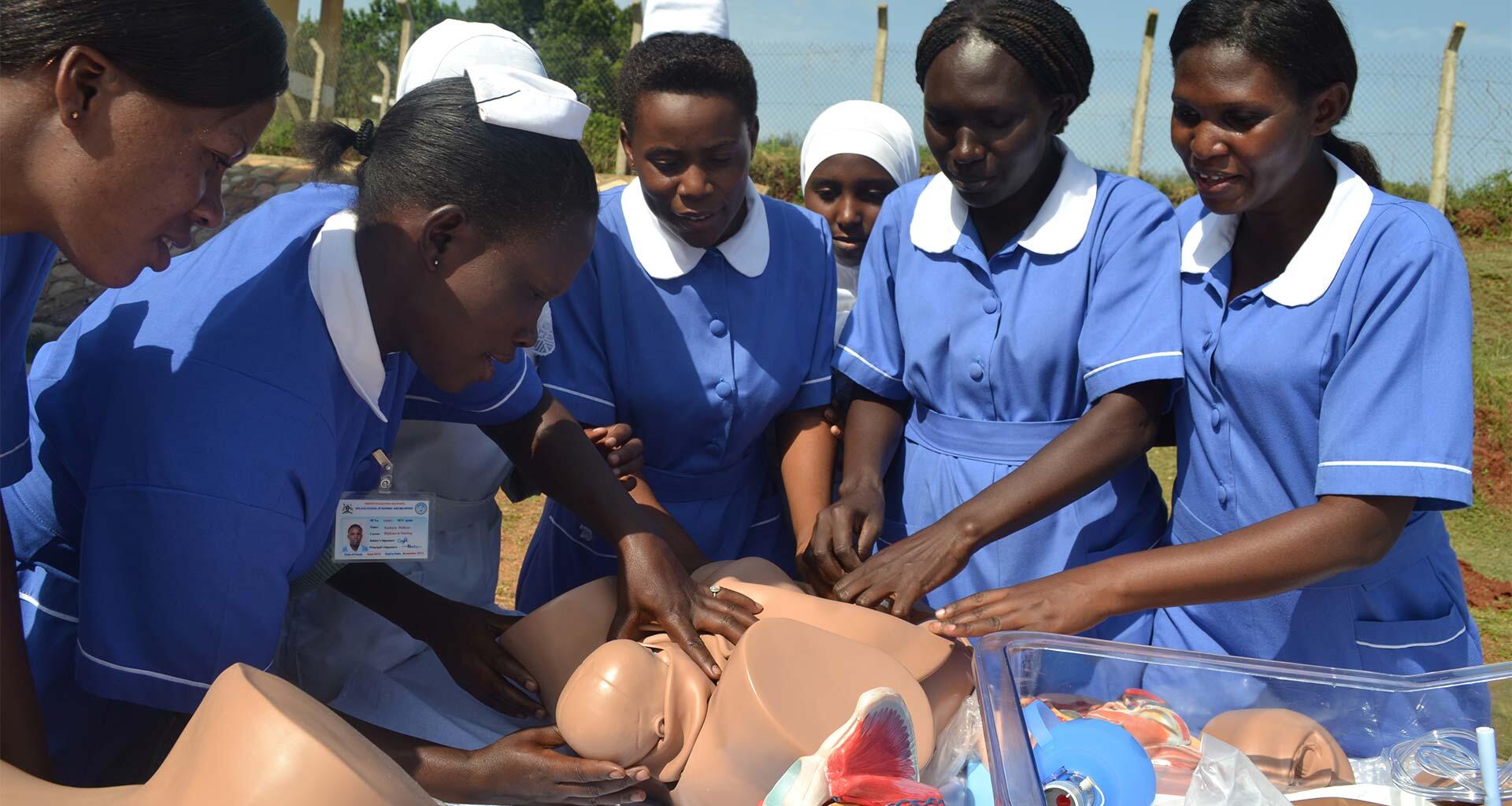

Our programmes – which operate in more than 150 countries and territories with 80 per cent of the world’s population – further the realization of sexual and reproductive rights and choices. We work with governments, health experts and civil society to train health workers, improve the availability of essential medicines and reproductive health services, strengthen health systems, and promote international maternal health standards.