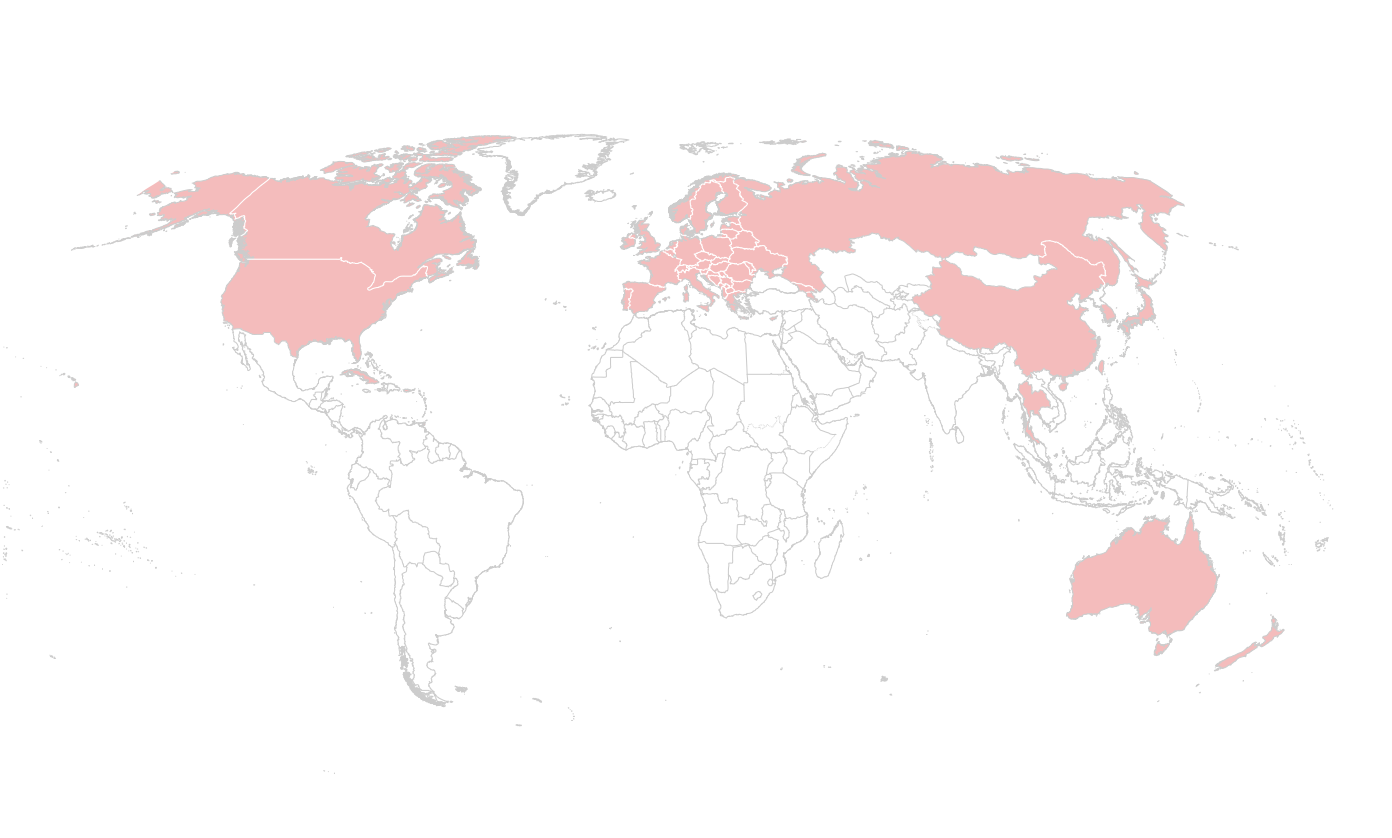

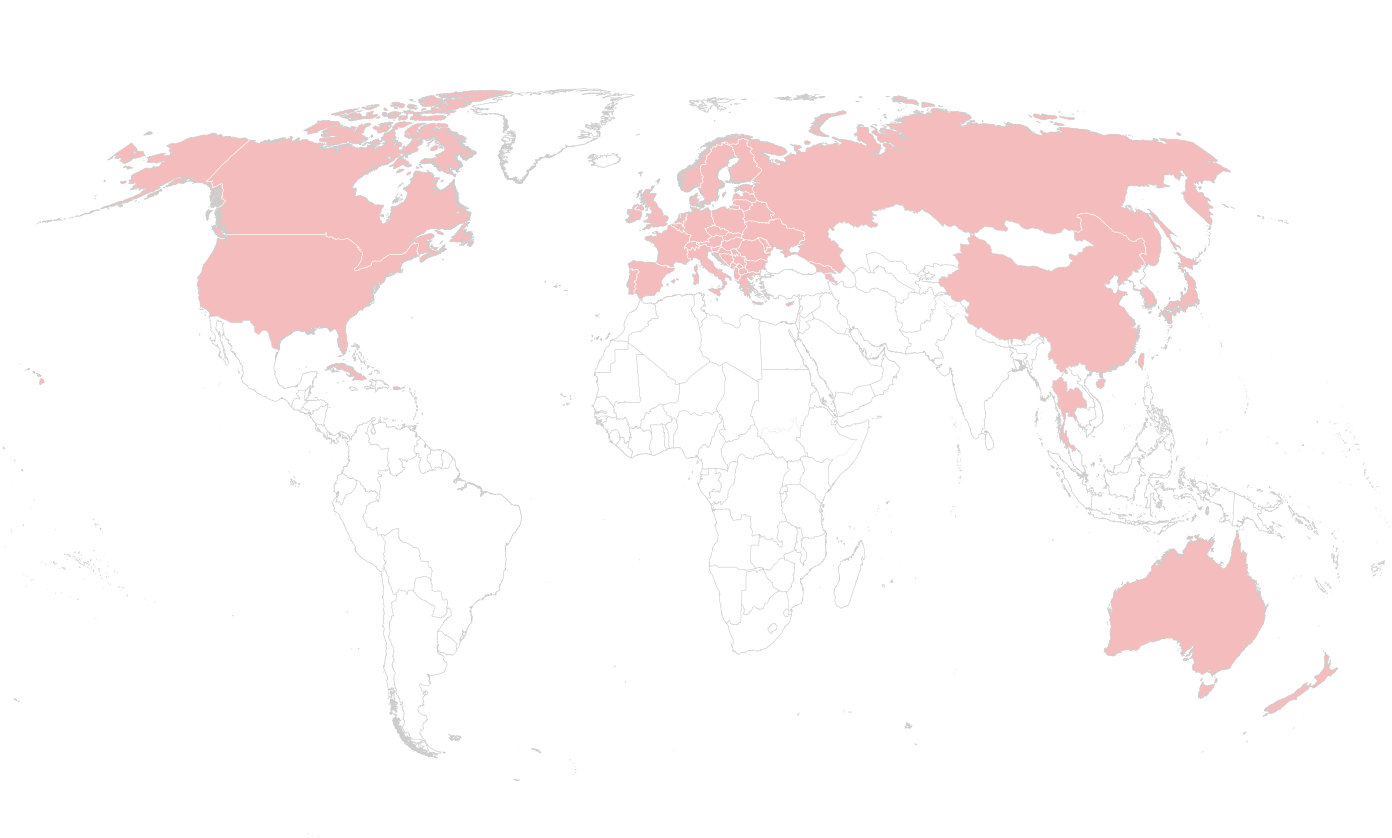

Can people in the world today have the number of children they choose, when they choose?

© Michele Crowe/www.theuniversalfamilies.com

© Michele Crowe/www.theuniversalfamilies.com

There are still millions of people who are having more–or fewer–children than they would like.

© Mads Nissen/Politiken/Panos Pictures

© Mads Nissen/Politiken/Panos Pictures

The extent to which individuals are able to exercise their reproductive rights determines the number of children they choose to have.

© Michele Crowe/www.theuniversalfamilies.com

© Michele Crowe/www.theuniversalfamilies.com

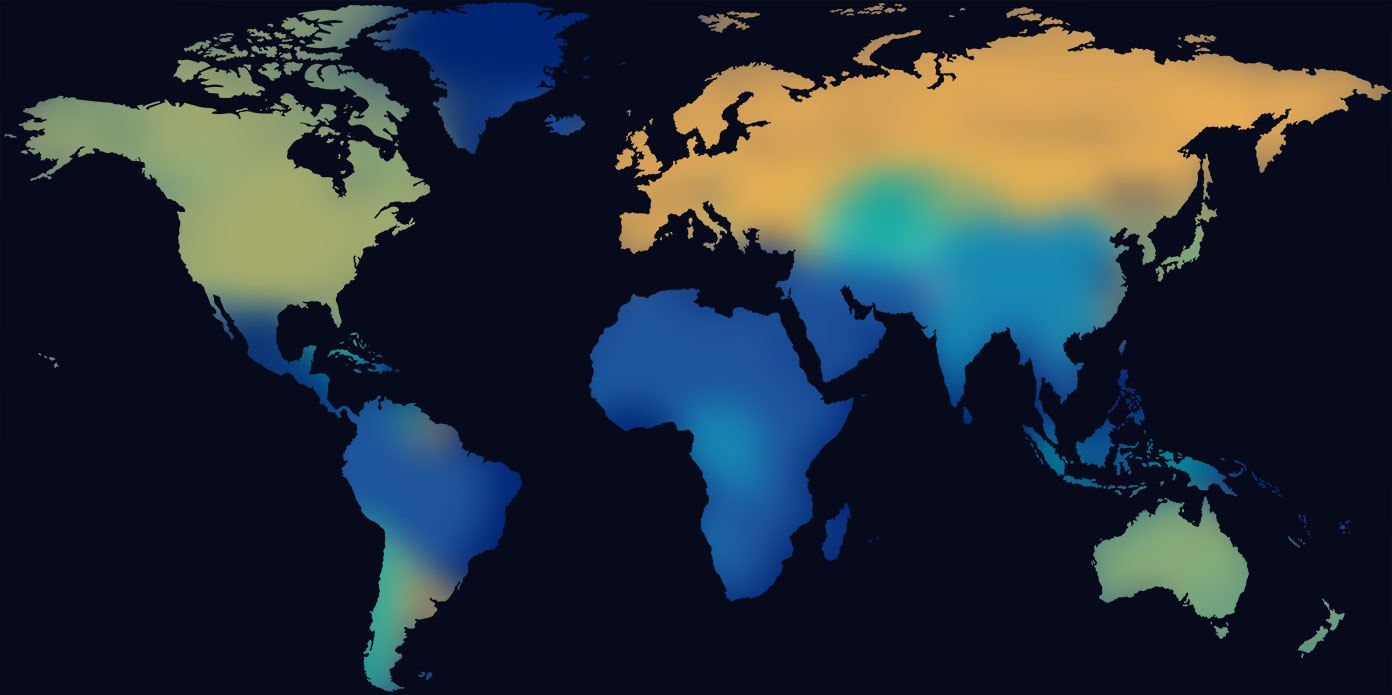

These choices, or lack thereof, are mirrored directly in fertility rates across the globe.

© Eriko Koga/Getty Images

© Eriko Koga/Getty Images

Never before in human history have there been such extreme differences in fertility rates among groups of countries.

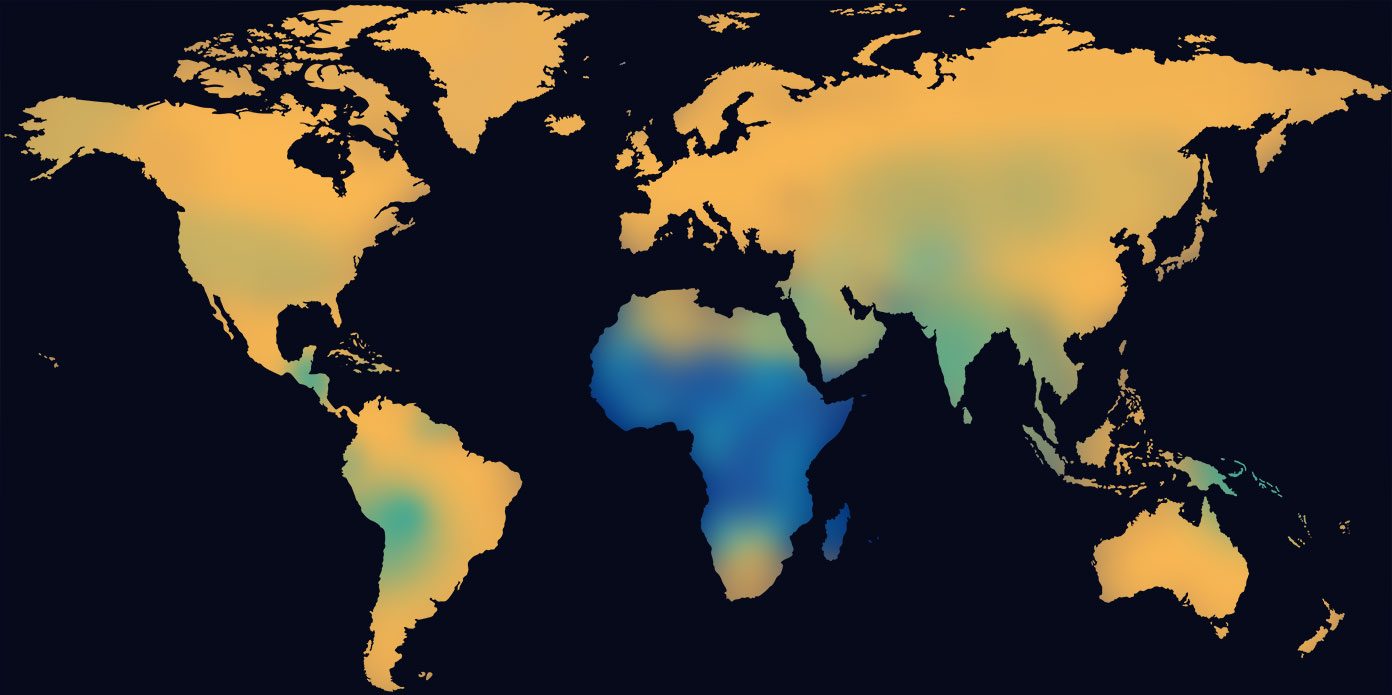

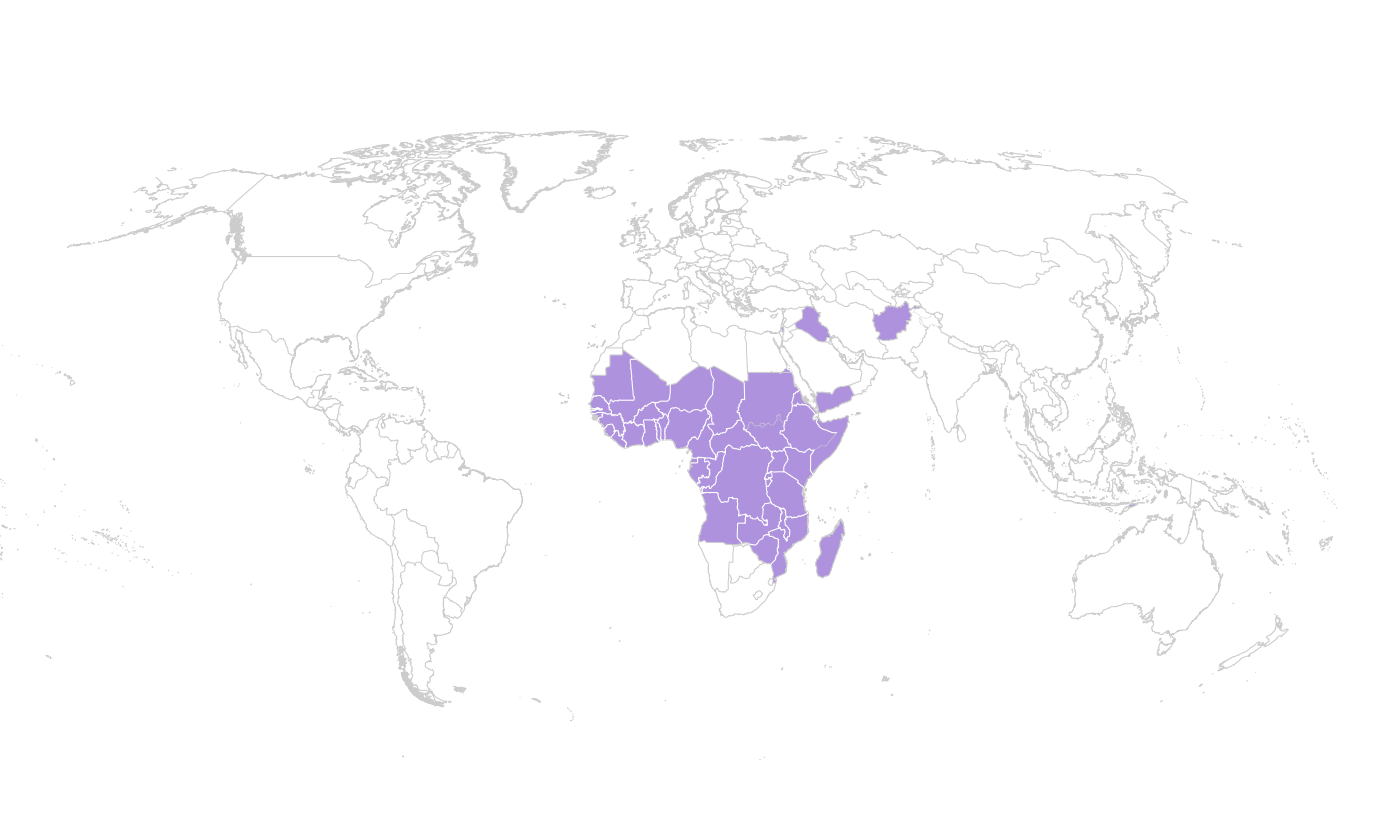

High Fertility

High fertility translates into faster population growth, with a disproportionate share of the population aged 15 or younger. High fertility rates pose challenges for governments struggling to meet the demand for education and health services, and to sustain development gains.

© Mark Tuschman

© Mark Tuschman

In high-fertility countries, economic, social, institutional and geographic barriers may prevent women from accessing quality family planning information and supplies. Barriers may be particularly insurmountable for young people. Together, these barriers stop millions of people from exercising their reproductive rights.

© Giacomo Pirozzi

© Giacomo Pirozzi

Women with at least a secondary education prefer to have fewer children compared to women with little or no education. Educated women are also in a better position to break the barriers to decent, paid employment later in life.

© UNFPA/NOOR/Bénédicte Kurzen

© UNFPA/NOOR/Bénédicte Kurzen

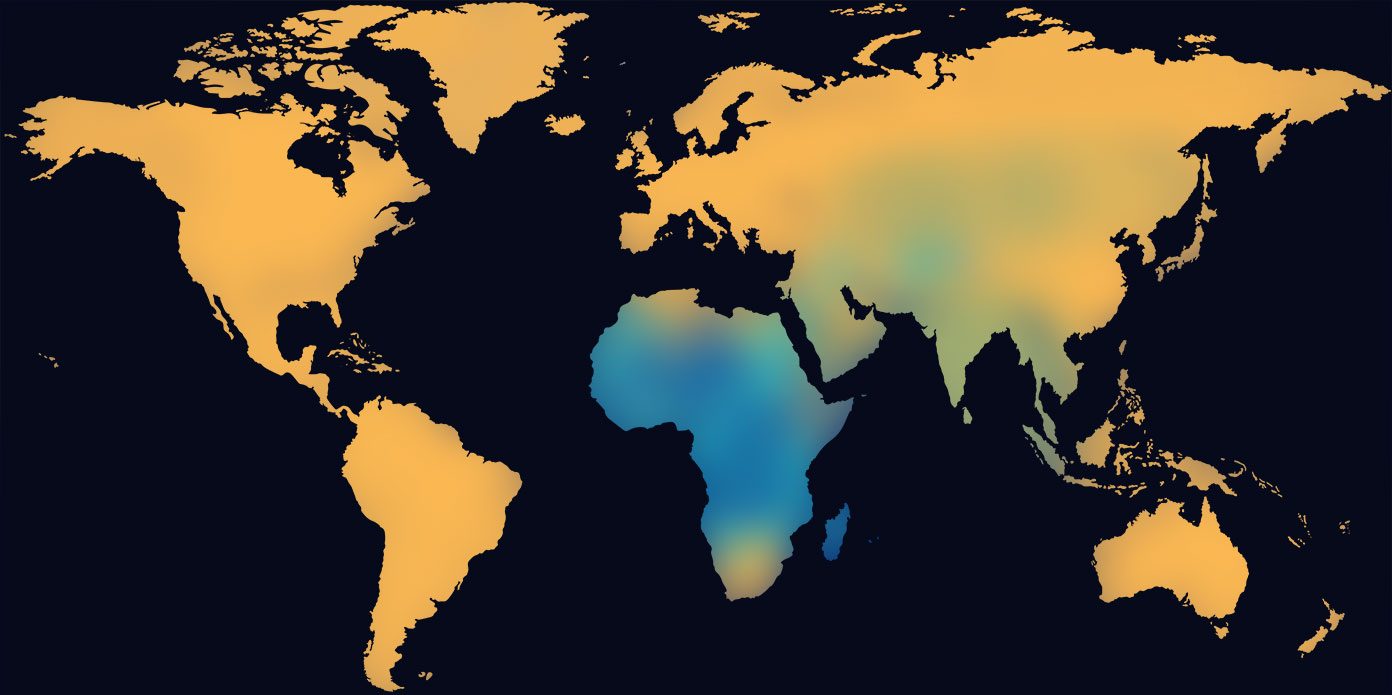

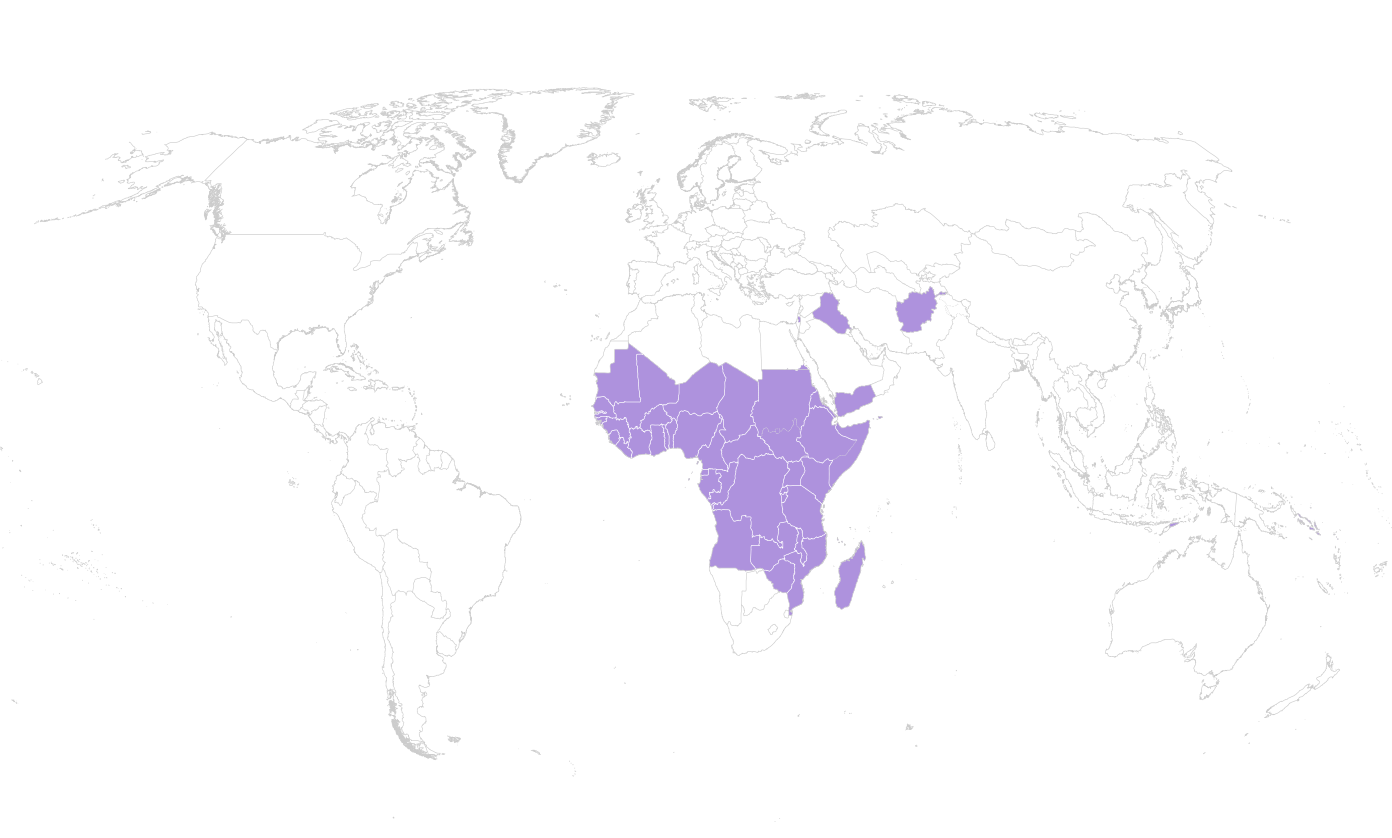

Middle Fertility

The countries where a woman has an average of three to four children are geographically and economically diverse and have followed different paths at different paces as their fertility rates declined.

© Chris Stowers/Panos Pictures

© Chris Stowers/Panos Pictures

A total fertility rate of three or four may mask large differences within countries, with wealthier people in urban areas having access to contraception, while rural, ethnic minorities have limited access to family planning programmes. Adolescents in some of these countries also have limited access to contraception information and services, resulting in comparatively higher rates of teenage pregnancy.

© UNFPA/Roger Anis

© UNFPA/Roger Anis

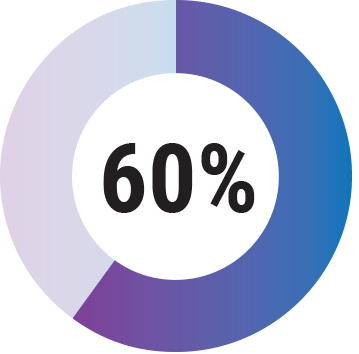

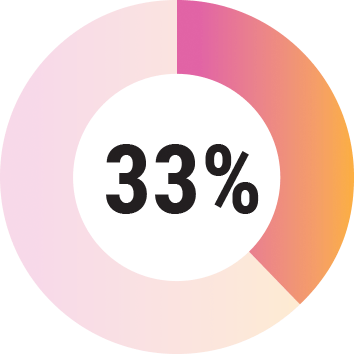

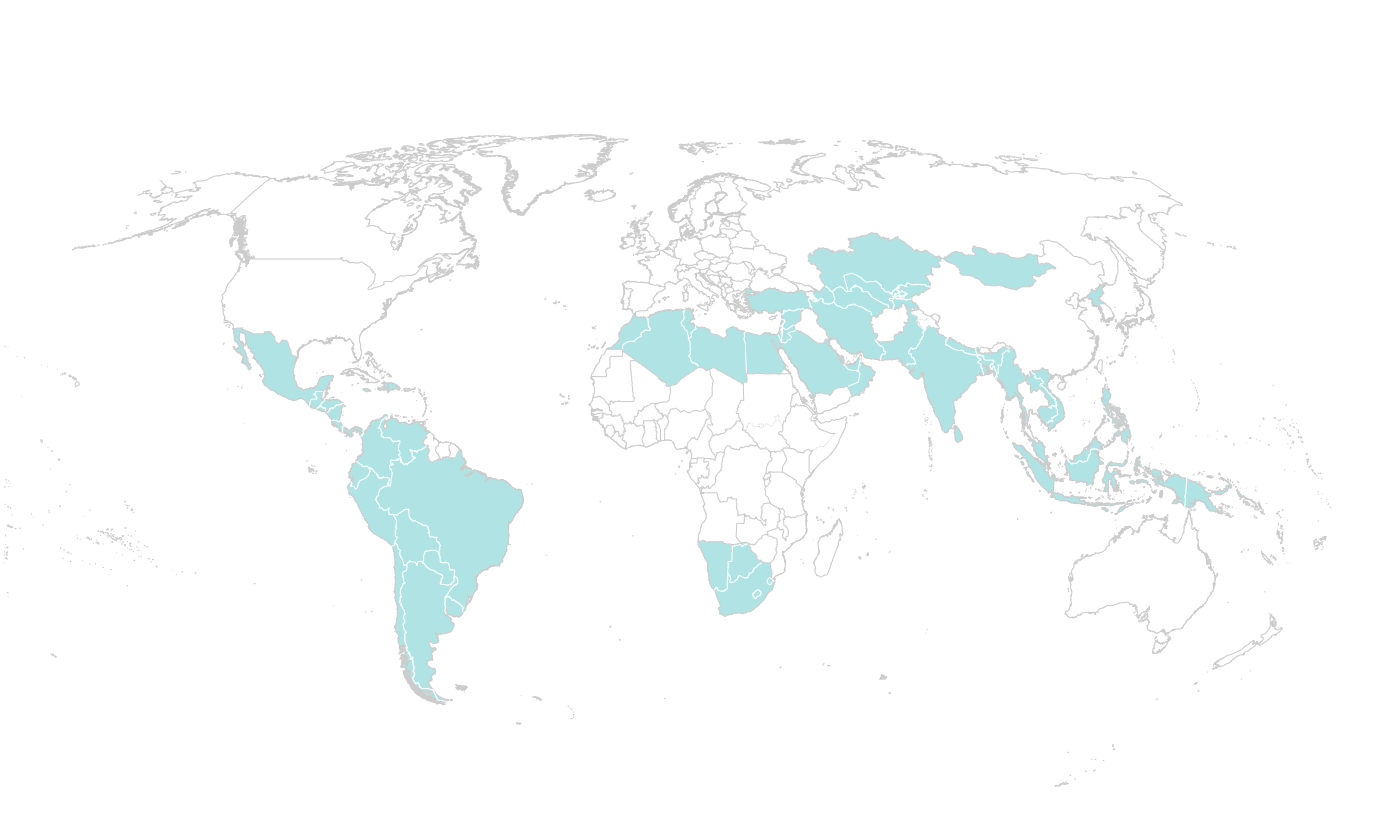

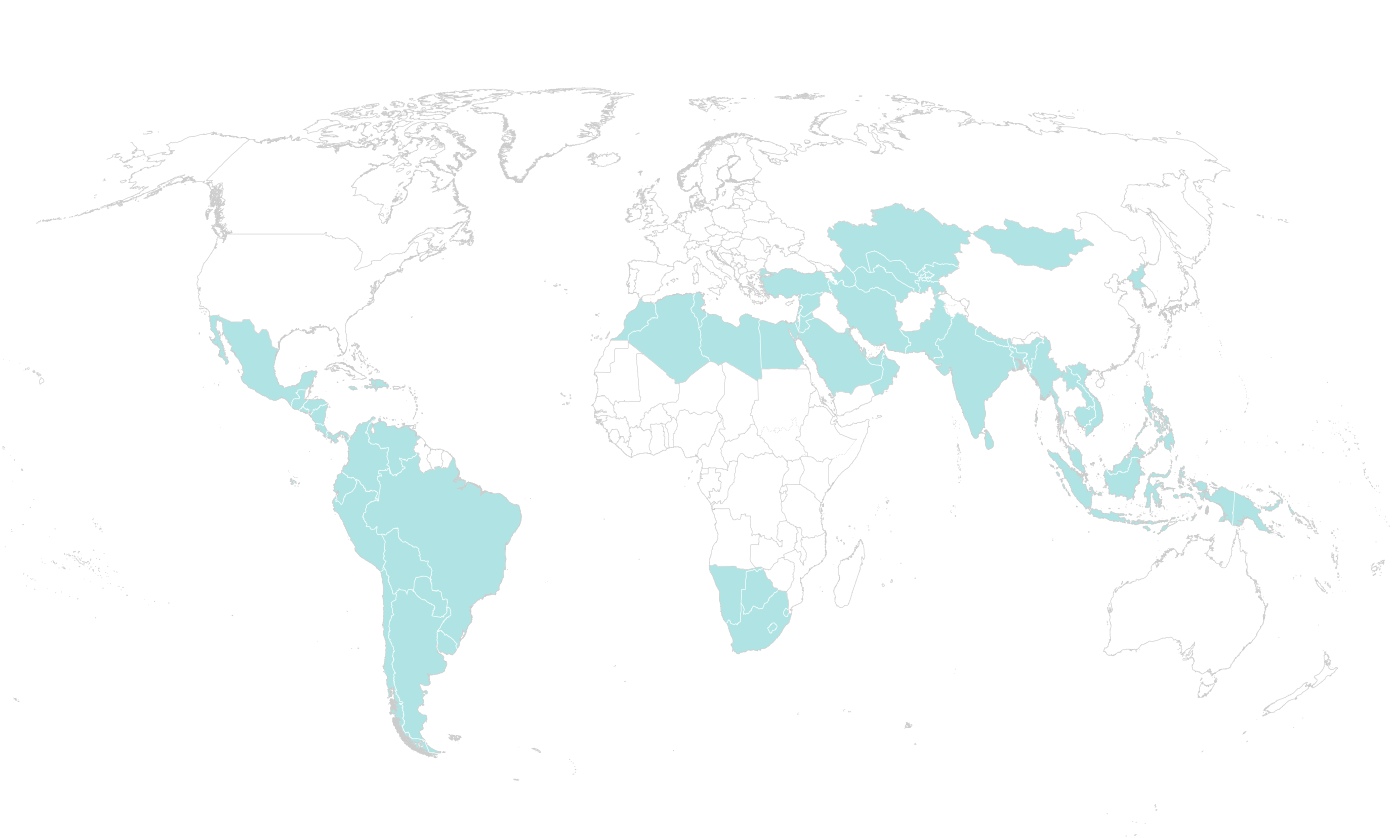

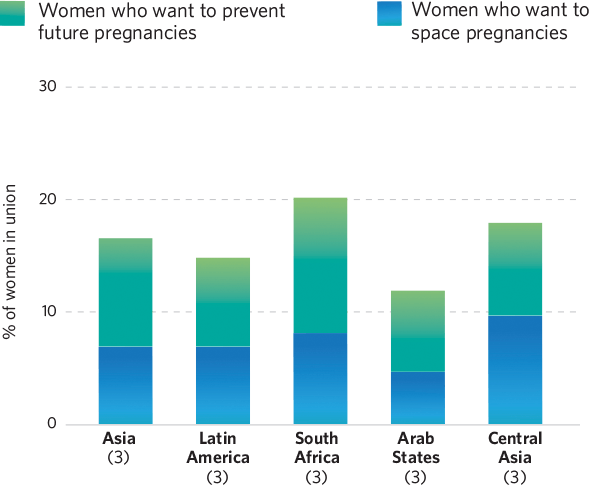

Percentage of women who have an unmet need for contraception

15 countries in 5 regions

In the 12 Latin American and Caribbean countries covered in this chapter, fertility rates among adolescents aged 15–19 and young people aged 20–24 are higher than rates for these age groups in other parts of the world with similar total fertility rates.

In some countries where fertility has been steadily declining, economic shocks, wars and other crises can cause fertility rates to dip suddenly as couples choose to delay having children and then rebound after the crisis, when stability and security return.

© Joshua Cogan/PAHO

© Joshua Cogan/PAHO

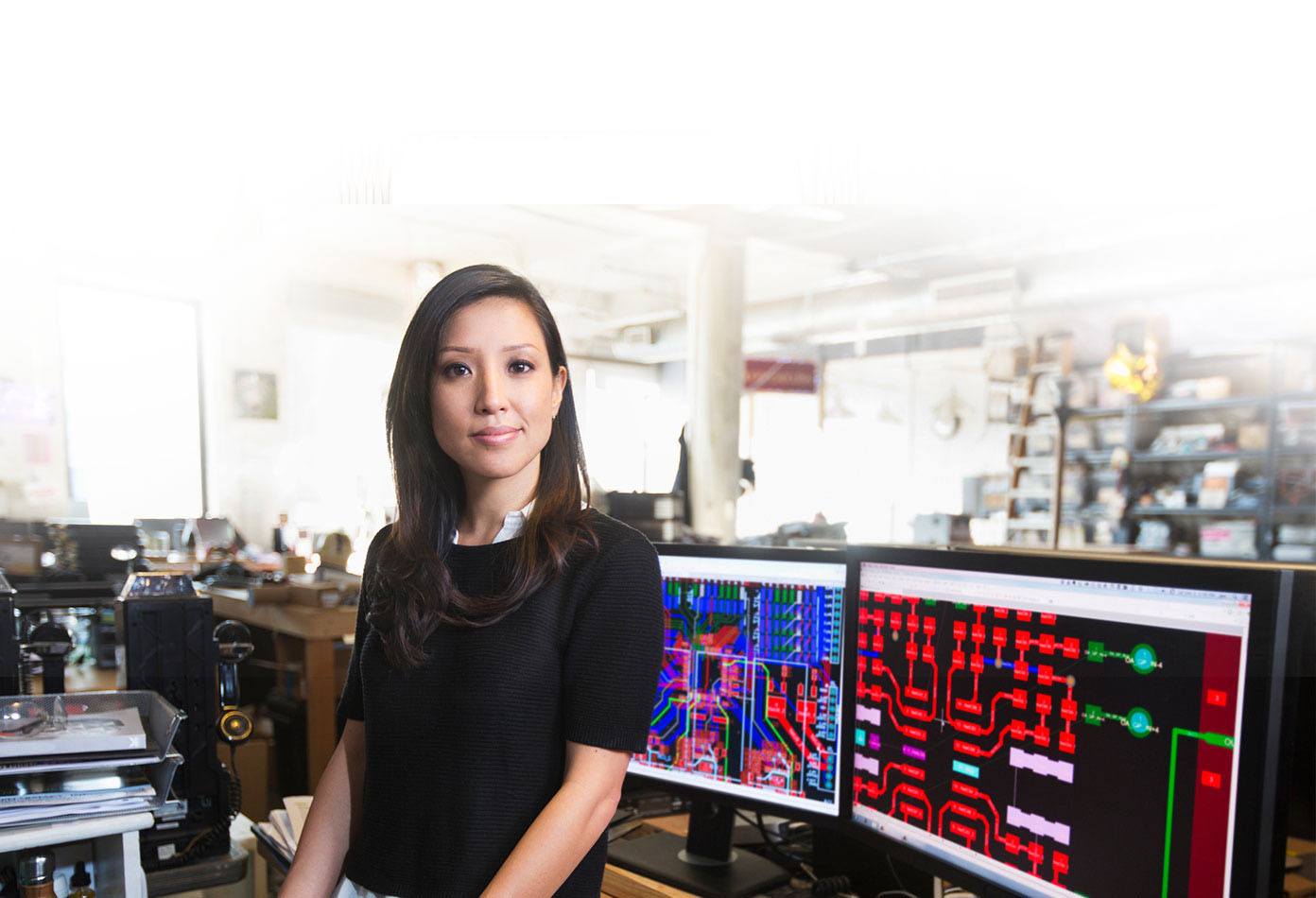

Low Fertility

Countries where fertility rates have been low for many years are generally more developed. Basic reproductive and other rights are mostly met. Challenges facing these countries typically include an increasing share of older people in their populations and higher associated health-care costs, as well as a shrinking labour force.

© UNFPA/Egor Dubrovsky

© UNFPA/Egor Dubrovsky

Current fertility rates of these countries indicate that women have become more effective in preventing pregnancies and spacing births. Where education and career are high priorities, marriage and childbearing may take a back seat. Women who opt to delay pregnancy until their late 30s or 40s are at greater risk of infertility and complications during pregnancy.

© Jasper Cole/Getty Images

© Jasper Cole/Getty Images

Long-standing gaps in support for balancing work and family life can inhibit women from having the number of children they want to have. Challenges that women in low-fertility countries face in exercising their reproductive rights include economic hardship, a lack of affordable housing, high childcare costs, and uncertain labour markets.

© Michele Crowe/www.theuniversalfamilies.com

© Michele Crowe/www.theuniversalfamilies.com

Fertility Matters

Amid today’s wide gaps between high and low fertility rates, both within and across countries, fertility issues and drivers vary hugely.

Much progress has been made in upholding reproductive rights. Yet today, no country can claim that all population groups enjoy these rights at all times. Almost everywhere, social, institutional and economic circumstances still deny some people the means to freely and responsibly have the number of children they want or have them when they want.

Each country needs to define the mix of services and resources it requires to uphold reproductive rights for all citizens, but there are some actions that apply to every country, regardless of fertility rate.

-

© Layland Masuda/Getty Images

© Layland Masuda/Getty Images

Consider conducting regular national reproductive rights “check-ups” to assess whether laws, policies, budgets, services, awareness campaigns and other activities are aligned with reproductive rights, as defined by the International Conference on Population and Development.