to top

She was born

to a poor family,

in a rural community,

in a poor country.

At age 10, she was pulled out of school to help with chores and care for her younger brother.

By the time she was a teenager, she was, like her mother, forced to marry an older man and start having children of her own.

At home, she learned how to perform household tasks and cultivate a field, but little else that might help her join the paid labour force.

Caught in a world where she has little say over her own life, she may one day get a glimpse of another world, one that is both better off and out of reach.

In today’s world, gaps in wealth have grown shockingly wide. Billions of people linger at the bottom, denied their human rights and prospects for a better life. At the top, resources and privileges accrue at explosive rates, pushing the world ever further from the vision of equality embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Inequality is often understood in terms of income or wealth—the dividing line between the rich and poor. But, in reality, economic disparities are only one part of the inequality story. Many other social, racial, political and institutional dimensions feed on each other, and together block hope for progress among people on the margins.

Two critical dimensions are gender inequality, and inequalities in realizing sexual and reproductive health and rights; the latter, in particular, still receives inadequate attention. Neither explains the totality of inequality in the world today, but both are essential pieces that demand much more action. Without such action, many women and girls will remain caught in a vicious cycle of poverty, diminished capabilities, unfulfilled human rights and unrealized potential—especially in developing countries, where gaps are widest.

Gini index

Gini coefficients show inequality in a single number. A value of zero reflects an idealized state, in which all individuals or households in a group have exactly the same wealth or income. On this chart, a value of 100 reflects absolute inequality, with a single individual or household monopolizing 100 per cent of economic power.

Aspects of inequality

Inequalities in reproductive health and rights

and economic inequality are intertwined

No country today—even those considered the wealthiest and most developed—can claim to be fully inclusive, where all people have equal opportunities and protections, and fully enjoy their human rights.

Sexual and reproductive health is a universal right

Having the information, power and means to decide whether, when and how often one becomes pregnant is a universal human right. That is what 179 governments agreed at the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994.

A universal right is one that applies to everyone, everywhere, regardless of income, ethnicity, place of residence or any other characteristic. But the reality is that today, across the developing world, that right is far from universally realized, with hundreds of millions of women still struggling to obtain information, services and supplies to prevent a pregnancy or to give birth safely.

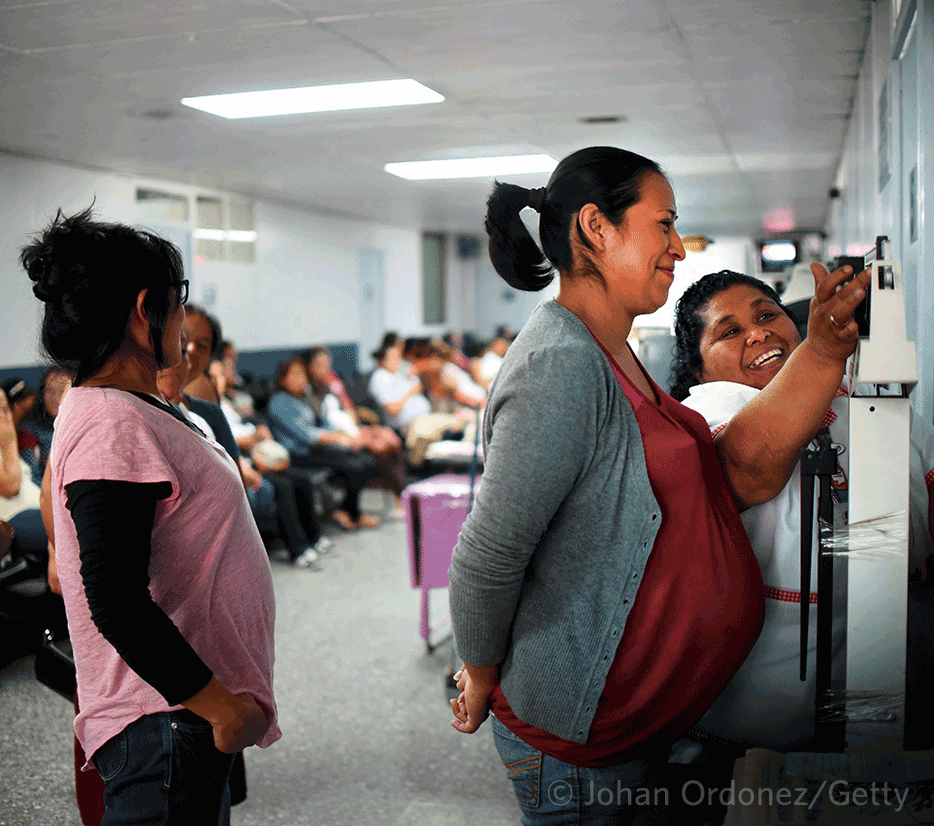

Whether a woman is able to exercise her reproductive rights depends in part on whether she lives in a city or a rural area, how much education she has and whether she is affluent or poor.

Economic inequality correlates with inequalities in sexual and reproductive health

Within most developing countries, women in the poorest 20 per cent of the population have, for example, the least access to sexual and reproductive health services, including contraception, while women at the top of the wealth scale generally have access to a fuller range of high-quality services.

The unmet demand for family planning in developing countries is generally greatest among women at the bottom of the wealth scale. Without access to contraception, poor women, particularly those who are less educated and live in rural areas, are at heightened risk of unintended pregnancy. This results in greater health risks and lifelong economic repercussions for herself and her children.

The unmet demand for family planning in developing countries is generally highest among women in the poorest 20 per cent of households

Annual change in proportion of births with skilled attendant, and in the difference between wealthiest and poorest quintiles, 2005–2011

Annual change in proportion of women having four or more antenatal visits, and in the difference between wealthiest and poorest quintiles

Annual change in proportion of demand for family planning satisfied by modern contraception, and in the difference between wealthiest and poorest quintiles

Each dot on these three charts represents a country. Countries in the top left quadrant are ones that have made more progress in overall access to services and in reducing inequalities among the poorest households over a 10-year period.

Average annual change in proportion of women receiving four or more antenatal visits

Average annual change in the absolute difference between wealthiest and poorest quintiles

Whether a woman is able to exercise her reproductive rights can influence whether she will realize her full potential and will be able to seize opportunities in education or compete for a job. Her options in life may be curtailed by limited options in sexual and reproductive health.

An unequal labour force

As fertility has declined worldwide, labour-force participation of women has increased in most regions. Where women participate in the labour force at high rates, the resulting trends have been towards lower fertility, due in part to the struggles of balancing educational and career aspirations with having and caring for children. In high-fertility countries, particularly the least developed countries, women’s enrolment in the labour force as wage and salaried employees remains low.

For women everywhere, pregnancy and child-rearing can mean exclusion from the labour force or lower earnings. The challenges are even greater for women who lack the means to decide whether, when or how often they become pregnant.

Gender inequality is pervasive worldwide, with negative or discriminatory attitudes, norms, policies and laws preventing women and girls from developing their capacities, seizing opportunities, entering the labour force, realizing their full potential and claiming their human rights.

Gender-unequal norms not only influence whether a woman enters the labour force but can also dictate which types of jobs she may pursue, determine how much she will be paid and hinder her advancement in the workplace. Countries with norms that prioritize employment for men over women have greater gender inequality in labour-force participation.

Do you agree?

Labour-force participation

There is widespread agreement that men and women should have equal access to a university education, but less so when it comes to equal access to employment when jobs are scarce.

The graphic below shows the percentage of respondents who DO NOT AGREE with the following statements:

'a university education is more important for a boy than for a girl' and

'when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women'.

- Rights to a job

- Gap between support

- University education

The grey area between the left and right points for each country represents the gap between public support or equal access to education and public support for equal access to employment when jobs are scarce.

Caucasus and Central Asia

Southern Asia, South-Eastern Asia and Eastern Asia

Western Asia

Northern Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa

أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي

Developed regions

Social institutions that put women and girls at a disadvantage in key spheres of their lives also put them at a disadvantage in entering the labour force.

Laws can exclude women

Laws can reflect or reinforce discriminatory norms and attitudes that block women’s access to the labour force or drag down their earnings relative to those of men. In 18 countries, men can legally prevent their wives from working outside the home, according to the World Bank. Laws in some countries limit women’s access to banking and credit, which can limit their earnings potential.

Laws—or their absence or inadequate enforcement—can affect the health and well-being of women, and thus influence women’s labour-force participation and their ability to earn an income. Forty-six of 173 countries examined in a World Bank report had no domestic violence laws, and 41 had no laws pertaining to sexual harassment. The World Bank also found laws protecting against “economic violence” are rare. Economic violence occurs when a woman is deprived of the economic means to leave an abusive relationship, because her partner either controls the economic resources or prevents the woman from having or keeping a job.

Pervasive gender inequality in categories of work

Statistics on overall labour-force participation rates mask substantial inequalities in the types of work that women and men are undertaking and the economic risks that some categories of workers face.

Once women are in the labour force, they account for a larger share of work in household enterprises and a smaller share of waged or salaried employees than their male counterparts.

In 18 countries, men can legally prevent their wives from working outside the home

Once in the paid labour force, women everywhere find themselves earning less than men for the same types of work; engaging more frequently in unskilled, low-wage labour; or spending less time in income-generating work and more time in unpaid caregiving work at home.

Inequality in reproductive rights, gender and earnings

Within any country, earnings for women compared with men depend on a variety of factors, including educational attainment, the extent of gender-discriminatory norms and practices in the home and the labour market, the range of available occupational opportunities, and how much say a woman has in decisions about whether, when and how often she becomes pregnant.

The gender wage gap is the percentage shortfall in the average wage of women relative to the average wage of men. Globally, the gender wage gap is about 23 per cent, or, in other words, women earn 77 per cent of what men earn, according to ILO. Worldwide, the gender gap has narrowed somewhat in recent years, but progress has been slow. At current trends, it will take more than 70 years before the gender wage gap is closed.

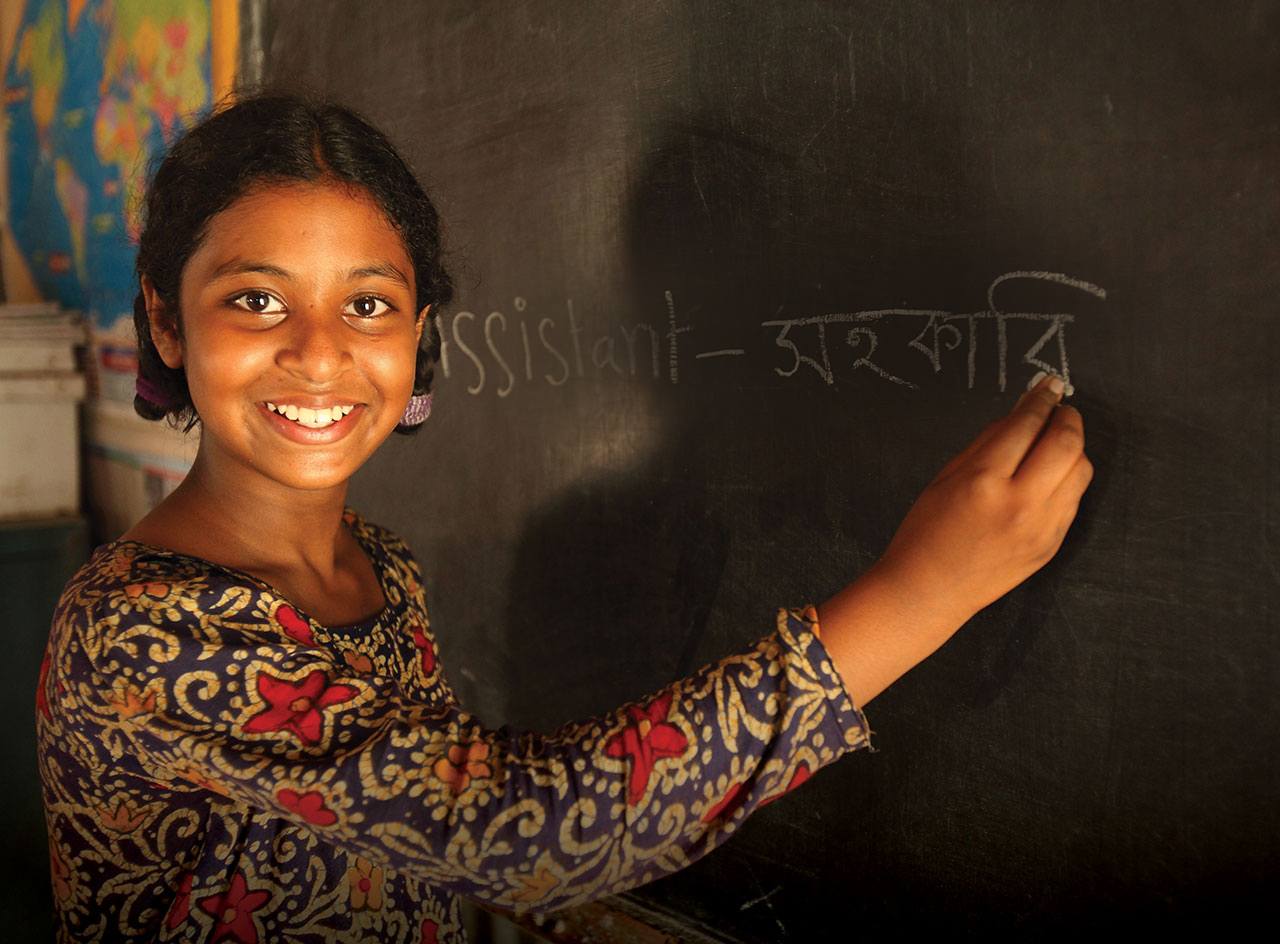

Gender inequality in education leads to lower earnings

Entry into the labour force and earnings depend in part on educational attainment, the quality of the education and the relevance of the education to the labour market. Gender inequality can result in worse educational outcomes and dim prospects for women’s earnings.

While there is near gender parity in primary education worldwide, the gender gap in enrolments in some countries is wide, which means that millions of girls of primary school age are not in the classroom. Higher educational attainment is correlated with higher earnings later in life.

Education has been documented to reduce the incidence of adolescent pregnancy. The longer a girl stays in school, the less likely she is to be married as a child or to become pregnant. This has long-term implications for labour-force participation and lifetime earnings.

Equal access to quality education not only addresses absolute deprivation by providing individuals with a pathway out of poverty, but also increases overall national productivity and innovation, by generating far greater opportunity for all people to develop their skills, find their niche and define their future areas of work. Increasing the collective capabilities of the population helps to grow national economies.

Globally, the gender wage gap is about 23 per cent, or, in other words, 77 per¢ of what men earn

When women are employed, their additional responsibilities for household work and care mean that they work longer days than men. In developing countries, women spend an average of nine hours and 20 minutes per day on paid and unpaid work, compared with men, who spend an average of eight hours and seven minutes per day on paid and unpaid work.

Motherhood penalty

In every part of the world, mothers who are in the labour-force earn less than women who do not have children. The motherhood wage penalty may linger even after children are grown, because mothers are likely to lose ground in earnings for taking time off during pregnancy or after giving birth.

Employers’ expectations about women becoming pregnant can contribute to the gender wage gap. According to Dr. Hilary Lips of Radford University, employers may justify paying women less because of a perception that women lack commitment to their jobs when they have the added work of family. ILO reports, some employers perceive all women as potential mothers and pass them over for more challenging assignments, or even promotions, because of a risk of unexpected pregnancy-related leave.

Lack of maternity leave or guaranteed job retention forces many women to choose between participating in the labour force and giving birth, or between their productive and reproductive roles.

Vicious cycle of lower earnings and diminished capacities

Inequality—regardless of the type—is the product of a range of forces in society that interact and create sets of constraints or behavioural boundaries for individuals. These constraints and boundaries limit options, access to resources and choices.

Gender inequality is one such force that results in constraints and boundaries for half the world’s population. Many of the inequalities in sexual and reproductive health and rights are intertwined with, or even driven by, gender inequality.

Worldwide, women’s earnings are lower than those of men. Lower earnings stem from gender inequality in education and health, and from unequal protection of rights. These inequalities result in diminished capacities for women, as well as in a more limited range of options and opportunities for jobs and livelihoods.

And, with lower earnings, women have fewer resources for critical services, such as family planning, which could empower them to enter the labour force and earn more once they are employed. This situation sets off a vicious cycle that can prevent women, their children and their children’s children from rising out of poverty.

Costs of inequality

Worsening inequalities

hold everyone back

Inequality blocks the path to the world we want. It allows development to benefit some but not others, marginalizes some groups and individuals, and distorts political, social and economic relations. Inequalities lead to social and geographic clustering of privilege and deprivation. This results in less social contact between these groups through school, work or housing, and diminished understanding, contributing to extremes in political discourse.

Throughout the developing world, the poorest women and adolescent girls are less able than their wealthier counterparts to exercise their reproductive rights and protect their health. Inequalities in sexual and reproductive health may be even more pronounced depending on place of residence—in a city or a rural area—and on level of education. Rural and less educated women typically have less access to services and worse reproductive health outcomes than more educated women in urban areas.

When health and rights are out of reach for a large share of a country’s population, everyone is harmed in some way. A poor woman who cannot access family planning, for example, may have more children than she desires. As a result, she may be unable to join the paid labour force and contribute to her country’s economic growth and development.

Inequalities in sexual and reproductive health and rights have costs to the individual, the community, nations and the entire global community.

Unequal reproductive risksAccording to the Guttmacher Institute, each year in developing countries, there are 89 million unintended pregnancies, 48 million abortions, 10 million miscarriages and 1 million stillbirths. An estimated 214 million women in developing countries have an unmet demand for family planning.

Data from 98 developing countries show that the unmet demand for family planning is greater among women who are poorer, rural and less educated than among their richer, urban, more highly educated counterparts. When poorer women in developing countries do become pregnant, their limited and unequal access to reproductive health care, as well as their unmet nutritional needs, can lead to serious complications for both mother and fetus.

Girls under age 15 account for 1.1 million of the 7.3 million births among adolescent girls under age 18 every year in developing countries. Most of the world’s births to adolescents—95 per cent—occur in developing countries, and nine in 10 of these births occur within marriage or a union. Child marriages are generally more frequent in countries where poverty is extreme and among the poorest groups within countries.

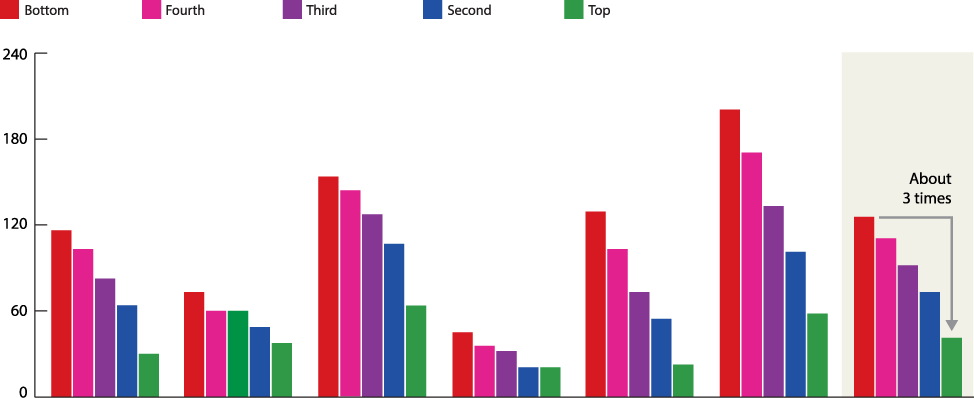

Adolescents (between the ages of 15 and 19) in the poorest 20 per cent of households in developing countries have about three times as many births as adolescents in the richest 20 per cent of households. Adolescents in rural areas have on average twice as many births (as a rate per 1,000 females) as their counterparts in cities.

Variations in adolescent birth rates within a country stem in part from inequitable access to sexual and reproductive health services. Adolescent girls typically have less access to contraception than adolescent boys because of discriminatory policies, judgmental service providers or prevailing attitudes about what is acceptable behaviour for girls.

A pregnancy can have immediate and lasting consequences for a girl’s health, education and income-earning potential, and often alters the course of her entire life.

95 per cent of the world's births to adolescents occur in developing countries

Adolescent birth rates, per 1,000 women (ages 15 to 19), by region and wealth quintile

Intersection of inequalities in health, education and gender

Despite progress towards gender equality in education over the past three decades, girls are still more likely than boys to be out of school at the primary level and even more likely not to be enrolled at the secondary Level, according to UNICEF and UNESCO. Lower enrolments, attendance and completion rates are the result of many social, geographic and economic factors that place girls at a disadvantage in education, especially as they enter adolescence.

When a girl is not in school, she misses out on opportunities to gain knowledge and build skills that may help her realize her full potential later in life. In addition, girls who are not in school may miss out on comprehensive sexuality education and life-skills training, where they could learn about their bodies, and about gender and power relations. In school, they could also build communication and negotiation skills, without which they will be additionally disadvantaged as they transition through adolescence into adulthood. Comprehensive sexuality education is a rights-based and gender-focused approach to sexuality education, whether in school or out of school. It is taught over several years, providing age-appropriate information consistent with the evolving capacities of young people.

Inequalities in sexual and reproductive health and economic inequalities

Inequalities in sexual and reproductive health correlate with economic inequality: women in the poorest wealth quintile of developing countries generally have least access to services essential for exercising their rights to prevent pregnancy, stay healthy during pregnancy and deliver safely.

Poverty excludes millions of women from life- saving services that are readily available to those in the top economic strata. This exclusion can lead to poor reproductive health outcomes, with repercussions not only for a woman’s health, but also for the well-being of her household, her community, and the nation’s economic and social development.

Inequalities in reproductive health and economic inequality may therefore be mutually reinforcing and have the potential to trap women in a vicious cycle of poverty, diminished capabilities and unrealized potential. Although the pathways between one dimension of inequality and another are not linear, the connections are clear.

Intersecting forms of inequality may have huge consequences for societies as a whole, with large numbers of women suffering ill health or being unable to decide whether, when or how often to become pregnant, and thus lacking the power to enter the paid labour force and realize their full potential. The damaging effects may span a lifetime for individuals and reach into the next generation.

Percentage of poorest females aged 7-16 who have never been to school

| Rank | Country | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | الصومال | 95 |

| 2 | النيجر | 78 |

| 3 | ليبيريا | 77 |

| 4 | مالي | 75 |

| 5 | بوركينا فاسو | 71 |

| 6 | غينيا | 68 |

| 7 | باكستان | 62 |

| 8 | اليمن | 58 |

| 9 | بنين | 55 |

| 10 | ساحل العاج | 52 |

Average years of education for the poorest 17-to-22-year-old females

| Rank | Country | Years |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | الصومال | 0.3 |

| 2 | النيجر | 0.4 |

| 3 | مالي | 0.5 |

| 4 | غينيا | 0.5 |

| 5 | غينيا-بيساو | 0.8 |

| 6 | اليمن | 0.8 |

| 7 | جمهورية إفريقيا الوسطى | 0.8 |

| 8 | بوركينا فاسو | 0.9 |

| 9 | باكستان | 1.0 |

| 10 | بنين | 1.1 |

Photo credit: © Mark Tuschman

When looking at the characteristics of those who are poor, it becomes clear that individuals in poverty are also those most likely to face other forms of inequality.

Compounding inequalities

The interconnected, multidimensional nature of inequalities—in income, between the sexes, in reproductive health and in education—often makes it difficult to determine which forces are at play and in which ways. However, all of these inequalities interact, and have long-term and compounding consequences for people around the world.

Economic inequalities are often evident in wide or growing differences in health outcomes, which reflect inequalities in opportunity; and in access to information, quality health care or other public goods. Such inequalities in opportunity and access underpin health inequalities throughout the world, via unequal access to information technology, health education, modern health care and the benefits of scientific progress.

Attempts to address inequalities in outcomes or opportunities fall short if they fail to address the long-standing structural gender inequalities faced by women and girls, which operate in all societies, and which reinforce both relative and absolute deprivations.

The effects of income inequality are amplified and reproduced because of gender inequality, making the gender poverty gap one of the most resilient inequalities worldwide.

Structural gender inequality denies women the right to decide whether, when or whom to marry; and whether, when or how often to become pregnant. This lack of choice limits women’s life trajectories early in life. The structural inequalities facing women and girls result in clustered and compounded inequalities that undermine the contributions of half the world’s people.

Path to equality

Actions for

an equal world

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its accompanying 17 Sustainable Development Goals are grounded in principles of rights, fairness, inclusiveness and equality. Included in the global vision for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is the notion of “shared prosperity” and “a world of universal respect for human rights and human dignity, the rule of law, justice, equality and non-discrimination ... and of equal opportunity permitting the full realization of human potential ...”.

Prosperity for all

The most promising ways forward may be those that tackle intersections among inequalities, among individuals, and within societies and economies. Among these are measures to realize reproductive rights and gender equality, with a particular and urgent emphasis on reaching people ranked among the poorest 40 per cent—the furthest behind.

Making reproductive health care universally accessible, for example, not only helps fulfil a poor woman’s reproductive rights, but also helps her overcome inequalities in education and income, with benefits that accrue to her, her family and her country.

Whatever the course, it is time for stepped-up action, because, the more entrenched the gaps become, the more difficult they will be to close. Progress must be fast and fair, and sustainable over time. A more equal world depends on it.

Making reproductive health care universal can help women overcome inequalities in education and income

Coming closer together

Pulling a world that is apart closer together will not be easy, but it is feasible. From the poorest communities to the most powerful nations, progress towards inclusion can be made. There is no justification for 800 women to die every day giving birth. Or for unwanted pregnancies to overwhelm the resources of the poorest families. Or for young people to watch their futures drain away because early marriage ends their education.

Reducing all inequalities needs to be the aim. Starting points may vary, but should be grounded in the notion that meaningful progress in one dimension can unleash multiple gains. In that respect, some of the most powerful contributions can come from realizing gender equality and women’s reproductive rights.

The 2030 Agenda has envisaged a better future. One where we collectively tear down the barriers and correct disparities, focusing first on those left furthest behind.