Colombia

Safe, culturally sensitive, empowering childbirth for Colombia’s Afrodescendent women

More than two decades ago, 18-year-old Shirley Maturana Obregón visited a hospital in Chocó, in Colombia’s Pacific region, seeking care for a case of gastritis. Despite the fact that she was nine months pregnant at the time, Ms. Maturana Obregón never considered staying on and giving birth there.

“It wasn’t the environment I wanted,” Ms. Maturana Obregón tells UNFPA. “I wanted my mum to be there, and what I heard [at the hospital] was that I was going to be alone.”

So she returned home and soon went into labour. Her mother and sisters were there to support her throughout the delivery – as was a partera, a traditional birth attendant and practitioner of knowledge ancestral to Colombia’s Afrodescendent community. “It was beautiful and unforgettable,” she says.

For Ms. Maturana Obregón, the decision to give birth with a partera reflected her personal and cultural priorities. But home births also often reflect a lack of other options. Chocó’s population – of which 80 per cent identifies as Afrodescendent – is disproportionately poor and remains largely disconnected from Colombia’s formal health-care system. Getting to a doctor can require travel across hazardous, conflict-affected terrain, or can simply cost too much.

The consequences of not delivering safely can be deadly, particularly for Afrodescendent women and girls. In Colombia, they are at more than double the risk of dying due to pregnancy and childbirth than their non-Afrodescendent counterparts. Yet in seeking to improve maternal health outcomes, the Colombian health system has sometimes alienated parteras and the cultural values they represent.

Parteras been derided as witches and herbalists, or portrayed as unhygienic and unprofessional. Historically, Colombian laws required anyone attending childbirth to be officially licensed by a medical institution, rules that led to the erasure of the work parteras do, isolating them from the medical establishment. Yet along Colombia’s Pacific coast, parteras are often the only health provider on hand. In one town in Chocó in 2021, national statistics show every birth was supported by a traditional birth attendant (DANE and UNFPA, 2023).

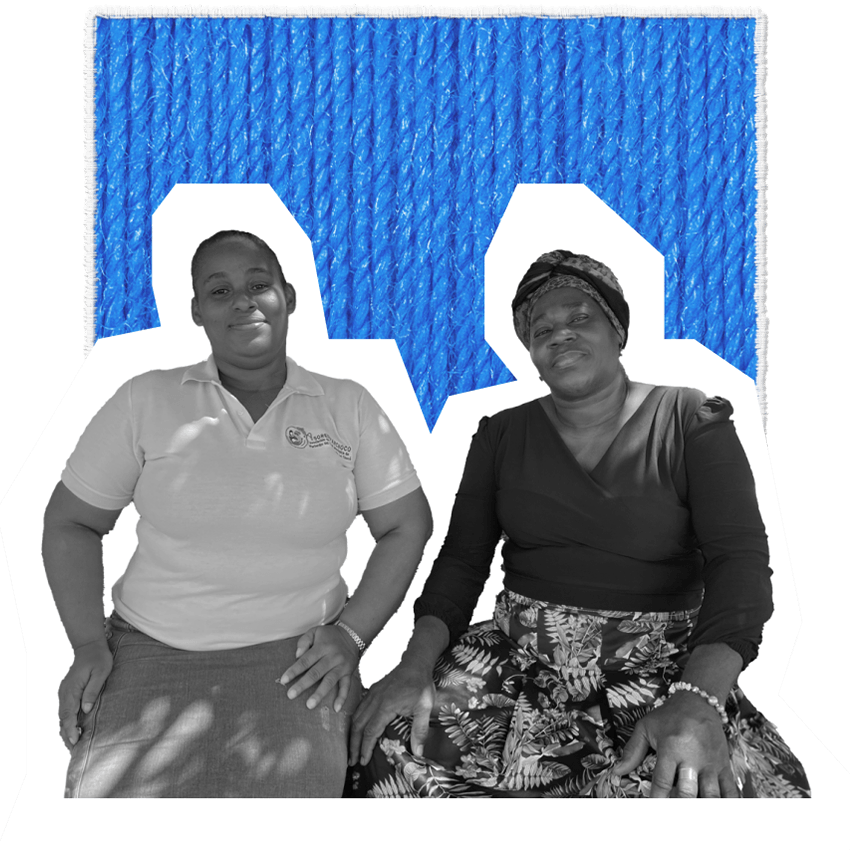

“Doctors treat us like everything [we do] is filthy,” says partera Francisca Córdoba, better known as Pacha Pasmo. “As I have told several doctors, you may have five years of experience, but you do not have the experience I have – I started attending births before you were born.”

But a new initiative is knitting health workers and parteras more closely together. In 2020, the Partera Vital project was launched, aiming to validate parteras’ often invisible work in providing culturally affirming care to pregnant and post-partum women, while also providing parteras with tools and skills to deliver their services safely to their communities and in conjunction with the formal medical system.

Through Partera Vital, Colombia’s national statistics agency worked together with UNFPA and local parteras associations to amend rules barring traditional birth attendants from registering newborns. Parteras received a mobile app allowing them to register births in the national birth registry; they also came together for training sessions aimed at improving risk identification during pregnancy and childbirth.

The project was first rolled out to 30 traditional birth attendants in Chocó. The parteras also received scales for weighing newborns, safe delivery kits containing items like clean sheets and gloves, and blood pressure monitors, which can help them identify life-threatening pregnancy complications. “If a partera sees that a pregnant woman’s blood pressure is high, they run to refer her,” Ms. Pacha says.

The project’s impact was immediately clear during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when statistics showed 34 per cent of births in Chocó were supported by parteras – nearly 50 per cent more than had been recorded in the previous year. Parteras petitioned the Government to be recognized as essential workers amid the crisis, a change that led to parteras receiving resources and equipment to care for their communities. Most recently, UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, designated midwifery in Colombia and other countries an integral part of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage.

Partera Vital’s introduction to Chocó has also corresponded with a major health advancement in the region: reduced maternal deaths. “We don’t know yet to what extent the empowerment of parteras has contributed to the national efforts to reduce maternal mortality in Chocó, but in 2023, maternal deaths dropped by nearly 40 per cent,” says UNFPA Colombia sexual and reproductive health adviser Jose Luis Wilches Gutiérrez.

Since delivering with a partera, Ms. Maturana Obregón has become one. “The people we serve – they want to experience having their children with a partera, because the partera puts her in the position she wants to give birth in,” she says. “We are there, making those women’s dreams come true.”

Artwork

Textiles blur the boundary between art and function, practicality and beauty. Women’s movements have long used textiles to draw attention to a range of issues – from body positivity to reproductive justice and systemic racism. Contemporary artists and women-led textile collectives continue this tradition by producing artwork which reflects their local environments and traditions. As it has for thousands of years, textile art continues to offer women around the world the means to connect with previous and future generations of women in their families and communities.

We would like to thank the following textile artists who contributed to the artwork for this report:

-

Nneka Jones

-

Rosie James

-

Bayombe Endani, represented by the Advocacy Project

-

Woza Moya

-

The Tally Assuit Women’s Collective, represented by the International Folk Art Market

-

Pankaja Sethi