Panama

Ngäbe women spark a revolution in women’s health and equality

“It’s three hours walking,” 25-year-old Eneida says, offering a casual description of the arduous mountain hike she had completed well into her ninth month of pregnancy to reach the maternity waiting facility, or casa materna.

Eneida lives in the remote Comarca Ngäbe Buglé, a region inhabited by the Ngäbe and Buglé indigenous groups, located high in the mountains of western Panama. There are only a few paved roads in the comarca, and they are pitted with holes. Some residents travel by horse. Most walk. Many pregnant women give birth at home for this reason. It is no coincidence that the comarca has the highest maternal death rate of any region in the country.

Eneida chose to wait out the final days of her pregnancy at the Casa Materna de San Félix, a maternity waiting home that provides food, health care and transport to safe delivery services. “I like it. This place is very nice,” she says.

The maternity waiting home is only one of many sexual and reproductive health services introduced to the comarca thanks to the organized efforts of the Ngäbe Women’s Association – a group that first convened 30 years ago with a very different goal. Back then, in the 1990s, the women of the community were seeking something else entirely: a market for their crafts.

“We began meeting and identifying our problems and our needs,” says Gertrudis Sire, president of the Ngäbe Women’s Association. It quickly became clear some of the biggest barriers to escaping poverty were not economic – they were reproductive. “The women in the community raised the problem that they had many children,” Ms. Sire recalls. She explains that whenever a woman was unable to feed her children, she referred to the problem as “July”, a reflection of how routine it was. “‘I have a lot of July in my house,’ people used to say. What is July? It was a way to identify the famine that was in the community. They said how can we avoid that situation? Have fewer children.”

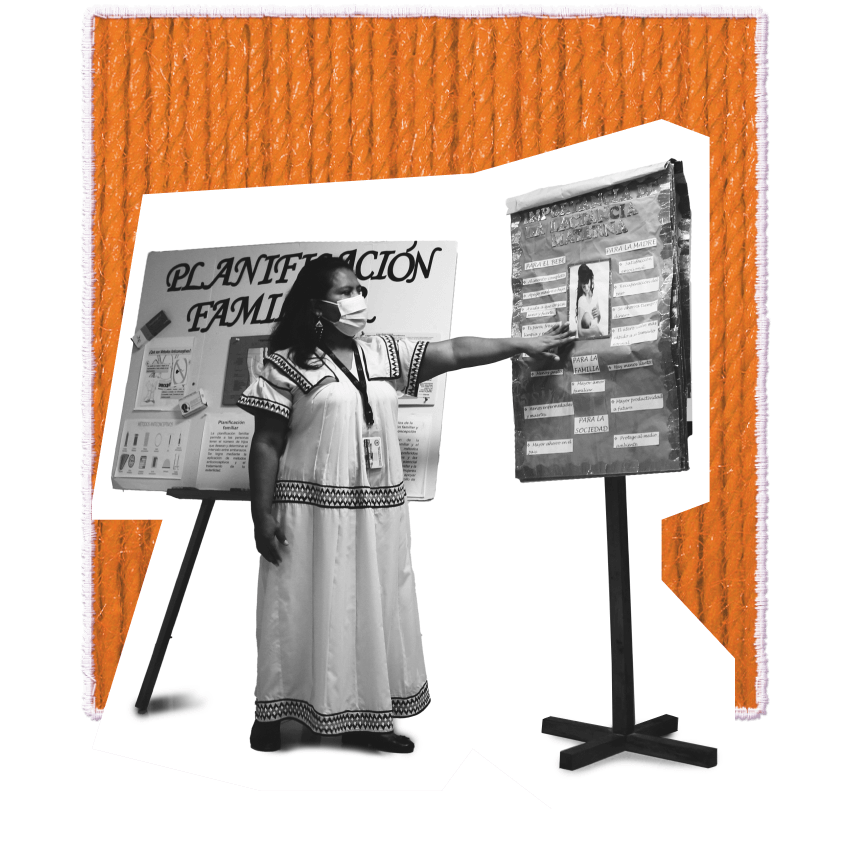

Other sexual and reproductive health needs also came to light. “We noticed that women were dying in their houses when giving birth. There was no plan to transport them because within the region there was no maternal and child hospital.” The association approached the Ministry of Health and UNFPA, and together they established a network of health workers to provide care and raise awareness about maternal health, contraception and child nutrition. Ms. Sire says, “We gave talks on these topics, and they felt it, they lived it.”

The mutually reinforcing relationship between gender equality, sexual and reproductive health, and economic empowerment was perhaps most notably recognized at the ICPD in 1994. But the experience of the Ngäbe Women’s Association shows that this realization was also taking place in the most remote corners of the world, as women began to plan their families and invest in a better future for themselves and their communities. The Ngäbe Women’s Association worked independently to unleash a virtuous cycle of reproductive autonomy, improved health and reduced poverty.

Eira Carrera, an intercultural interpreter at the José Domingo De Obaldía Maternal and Infant Hospital, began her career as a health promoter in the comarca. “That was in ’96, ’98,” she recalls. “The topics we covered as health promoters were sexual and reproductive health, which involves sexually transmitted infections, Pap smears, everything related to sexual and reproductive health, family planning… domestic violence, even responsible fatherhood.” The messages were better received among women than among men. While the women were generally eager to benefit from family planning – “because that was their need,” Ms. Carrera says – men were less receptive. “Men did not want this resource.”

There has been progress in the three decades since. Asked if Ngäbe women would say they make their own decisions about contraception, Ms. Carrerra says, “Out of 10 women, roughly 8 can say yes.” But there is still a long way to go. The issue of machismo is greatly compounded by persistent ethnic discrimination facing the community. Not long ago, Ngäbe community members were expected to sit at the back of the bus when travelling outside the comarca. Even today, job opportunities are scarce, and many Ngäbe men survive as migrant labour for coffee plantations.

For women, this overlap between ethnic marginalization and gender inequality continues to be deadly. “The majority of maternal deaths are specifically because the husband has not been able to take his wife to get care,” says Humberto Rodríguez, a nurse in charge of the Nole Duima District, describing deaths among women whose husbands were travelling when they went into labour. “The husband is not at home at that moment, and the decision is not hers.”

Ngäbe women used to be disempowered by health systems as well, Ms. Carrera says. “Doctors took the file, treated the woman and if she refused, the woman did not receive the care she needed or she received it in a forced, obligatory manner that would violate her rights… Today, that has totally changed.” Ms. Carrera now interprets between the health staff, who speak Spanish, and the patients, who speak Ngäbe. She also trains hospital personnel to engage in a culturally sensitive way. Women treated with dignity and information will often consent to care, Ms. Carrera says. “If she does not accept, that is respected.”

She wants women to understand bodily autonomy extends to their relationships, as well. “I give a talk here to mothers, saying you are not obliged to have sexual relations with your husband against your will. This is called sexual abuse,” Ms. Carrera explains. “We still have to work a lot on that.”

But these issues are not unique to the Ngäbe community, Ms. Sire emphasizes. “The problem is everywhere,” she says. “There will always be this machismo thing… and discrimination will never end, because that is everywhere… But people like us in the Association, we have been trained by it. We already have an armour.”

Eneida, the woman awaiting the birth of her third child, has such an armour – though she is open and smiling rather than defensive. Her armour is her confidence. Asked whether her partner would support her decision about family planning, there is no question: “Yes. Yes. I will be supported. Yes,” Eneid says. “With whatever I want.”

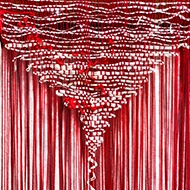

Artwork

Textiles blur the boundary between art and function, practicality and beauty. Women’s movements have long used textiles to draw attention to a range of issues – from body positivity to reproductive justice and systemic racism. Contemporary artists and women-led textile collectives continue this tradition by producing artwork which reflects their local environments and traditions. As it has for thousands of years, textile art continues to offer women around the world the means to connect with previous and future generations of women in their families and communities.

We would like to thank the following textile artists who contributed to the artwork for this report:

-

Nneka Jones

-

Rosie James

-

Bayombe Endani, represented by the Advocacy Project

-

Woza Moya

-

The Tally Assuit Women’s Collective, represented by the International Folk Art Market

-

Pankaja Sethi